Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

Understanding Nasal Trauma

Injuries to the nose are among the most common injuries affecting the upper respiratory tract. This high frequency is due to the prominent and relatively unprotected location of the nose on the face. Nasal trauma can range in severity and is generally classified by the nature of the damage: bruises (contusions), fractures, and open wounds (lacerations).

Prevalence and Types of Nasal Injuries

Isolated trauma to the external nose is the most frequently encountered type. The specific nature of a nasal injury largely depends on the force and direction of the impact, as well as the characteristics of the traumatic agent (e.g., blunt versus sharp object). Injuries to the nasal skeleton can result in cracks (fissures), complete fractures, or dislocations of the nasal bones and cartilages. The nasal bones themselves and the nasal septum are most often affected by fractures. Occasionally, the frontal processes of the maxilla (upper jaw bone) are also involved.

Mechanisms and Patterns of Nasal Fractures

- Lateral Impact: When the nose is struck from the side, the edge of the ipsilateral nasal bone is often injured, the nasomaxillary suture line (nasolabial articulation) can be disrupted, and the entire nasal pyramid may shift to the contralateral side.

- Frontal Impact: A direct frontal blow can cause the nasal bones to be pushed inward (depressed fracture), leading to a flattened appearance of the nasal dorsum (bridge). If the nasal bones are significantly impacted and the nasal vault (roof) is reduced in height, the bony part of the nasal septum is usually deformed as well. This often results in a C-shaped or S-shaped septal deviation, with a concavity on one side and convexity on the other. In children, such deformities can worsen with continued facial growth.

- Cartilaginous Injury: Sometimes, particularly with impacts to the lower, more mobile part of the nose, the quadrangular cartilage of the septum is damaged (e.g., fractured, dislocated from the vomerine groove or maxillary crest). Subluxation (partial dislocation) of the nasal cartilage can be very demonstrative. The cartilaginous part of the external nose may not show obvious deformity initially due to its elasticity, even if the underlying septum is injured. Post-traumatic perichondritis (inflammation of the cartilage covering) can lead to subsequent drooping of the nasal tip.

- Injuries in Preschool Children: A specific feature of nasal injuries in preschool children, whose bone sutures are less resistant than the bones themselves, is the separation of these sutures (diastasis). For example, a frontal impact can cause the nasal bones to be driven inwards and the nasal vault to flatten due to separation of the internasal suture (between the two nasal bones).

Impact on Olfaction and Nasal Development

In cases of injury to the nose, paranasal sinuses, or other bony formations of the skull, simultaneous injury to the olfactory analyzer (sense of smell apparatus) in its various parts is possible. This can occur due to squeezing or shearing of the delicate olfactory filaments (which pass through the cribriform plate) by displaced bone fragments. Impairment of smell can also result from hemorrhages into the olfactory region of the nose (superior nasal cavity), followed by the formation of scar tissue that compresses the olfactory filaments.

With the growth of a child, pre-existing traumatic deformities of the nasal bones and cartilage can become more pronounced, leading to progressive cosmetic and functional issues.

Symptoms of Nasal Trauma

Following a nasal injury, a variety of symptoms may be observed:

- Pain: Localized to the nose and surrounding facial area.

- Epistaxis (Nosebleed): Common due to mucosal tearing and fracture of vascularized bone/cartilage.

- External Deformity: Visible asymmetry, deviation, flattening, or depression of the nasal bridge or tip.

- Swelling (Edema): Significant swelling of the soft tissues of the nose, cheeks, and eyelids often develops rapidly.

- Ecchymosis (Bruising): "Black eyes" (periorbital ecchymosis) are common, even without direct orbital injury, due to subcutaneous hemorrhage. Bruising may also be present over the nasal bridge and cheeks.

- Nasal Obstruction: Difficulty breathing through the nose due to internal swelling, septal deviation, hematoma, or dislodged fragments.

- Crepitus: A crackling or grating sensation felt or heard on palpation of the nasal bones if they are fractured and mobile. This may be difficult to detect on the 2nd-3rd day due to significant soft tissue edema.

- Subcutaneous Emphysema: If a fracture of the nasal bones involves a tear in the underlying mucous membrane, air can escape into the subcutaneous tissues, leading to swelling and a crackling sensation, particularly around the eyelids.

- Impaired Sense of Smell (Hyposmia/Anosmia): Can occur due to direct trauma to the olfactory region, obstruction of airflow to this area, or damage to olfactory nerve filaments.

- Watery Eyes (Epiphora): If the nasolacrimal duct system is obstructed or injured.

- Headache and Fever: May be present, especially with more significant trauma or associated infections.

Impairment of smell following a nasal injury is more pronounced when nasal breathing is significantly difficult or if the olfactory cleft (the narrow space leading to the olfactory epithelium) is closed off by swelling or deformity. A decrease or complete absence of smell is more often observed on the side of the injury. If this impairment is caused solely by a reactive swelling of the nasal mucous membrane or by hemorrhage, the sense of smell may subsequently improve on its own or recover completely as the inflammation resolves. However, if the injury involves direct trauma to the bones of the olfactory region and compression or transection of the olfactory filaments (especially with fractures), the impaired sense of smell is, as a rule, persistent, and its improvement occurs relatively rarely.

Diagnosis of Nasal Trauma

The diagnosis of open injuries to the nose (e.g., lacerations) is usually straightforward. With isolated injuries involving only the skin of the nose in the form of bruises, abrasions, or contusions, often no additional extensive examination is required beyond clinical assessment.

However, if a closed nasal trauma (without open wounds) is suspected, diagnosis can be more challenging due to rapidly developing soft tissue edema, which can obscure underlying bony or cartilaginous deformities. Diagnostic steps include:

- Clinical Examination: Careful inspection for external deformity, palpation for tenderness, crepitus, and abnormal mobility of nasal bones. Anterior rhinoscopy (and nasal endoscopy if available) to assess the nasal septum for deviation, hematoma, or laceration, and to evaluate the nasal passages and turbinates.

- Imaging Studies:

- X-rays: Radiographs of the nasal bones (typically lateral and Waters views, or a specific nasal bone series) are often taken in cases of suspected fracture of the nasal bones or septum. They can show fracture lines and displacement.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: CT of the facial bones (including nasal bones and paranasal sinuses) provides more detailed information, especially for complex fractures, involvement of adjacent structures (sinuses, orbits, skull base), septal fractures, and is particularly useful if surgical intervention is planned.

Treatment of Nasal Trauma

Management depends on the type and severity of the injury.

Initial Management and Reduction Techniques

- Control Bleeding: Apply direct pressure, cold compresses. Topical vasoconstrictors may be used.

- Pain Management: Analgesics like acetaminophen or NSAIDs.

- Reduction of Nasal Fractures: If nasal bones are fractured and displaced, reduction (realignment) is often necessary to restore normal appearance and airway function. This is ideally performed within 7-14 days of injury, after initial swelling has subsided but before fractures begin to heal in a displaced position.

- Closed Reduction: Performed under local or general anesthesia. Displaced bone fragments are manipulated back into position using internal instruments (e.g., Boies elevator, Asch forceps) and external digital pressure.

- Open Reduction: May be required for complex fractures, significantly displaced septal fractures, or if closed reduction is unsuccessful. Involves surgical incisions for direct visualization and fixation of fragments.

- Fixation:

- External Fixation/Splinting: After reduction, an external nasal splint (e.g., plaster, thermoplastic, or metal) is often applied to maintain the position of the nasal bones. Tight gauze rollers applied along the lateral slopes of the nose and held with adhesive plaster, or custom-modeled fixators for children, can also be used.

- Internal Fixation/Packing: Internal nasal packing (e.g., with gauze tampons soaked in antibiotic ointment like synthomycin or streptocidal emulsion 5-10%) may be used to support the reduced bones and septum, and to help control bleeding.

- Management of Septal Injuries: Septal hematomas require prompt incision and drainage to prevent cartilage necrosis and abscess formation. Displaced septal fractures may need reduction and splinting.

- Wound Care: For open wounds, meticulous cleaning, debridement of non-viable tissue, and primary surgical closure according to generally accepted rules are performed. It is important to preserve as much viable tissue as possible. Superficially located foreign bodies are removed. Deeply embedded foreign bodies should be removed with great care in an operating room setting where bleeding can be managed.

Management of Associated Injuries and Complications

- Tetanus Prophylaxis: For contaminated wounds or crushing injuries, 0.5 ml of purified adsorbed tetanus toxoid is injected subcutaneously (after a test dose if indicated). If no adverse reaction, purified tetanus toxoid (e.g., 3000 IU) is injected into another site with a different syringe.

- Subcutaneous Emphysema: Usually resolves spontaneously without specific treatment as the trapped air is absorbed.

- Edema: Cold compresses (ice pack) can help reduce swelling.

- Nasal Obstruction: If breathing through the nose is absent or difficult, short-term use of nasal decongestant drops (e.g., 0.5% naphazoline solution) may be prescribed.

- Shock Management (if present): Children with nasal injury in a state of shock require maximum rest, warming, pain relievers, antihistamines (e.g., pipolfen, suprastin), and cardiac support drugs if necessary.

- Concussion Management: If nasal damage is combined with a brain concussion, complete rest with strict bed rest for at least 2-3 weeks is indicated. An ice pack is placed on the head. Dehydration therapy (e.g., 20% glucose solution, 25% magnesium sulfate solution intravenously or intramuscularly) and symptomatic treatment are used. Antibiotics and sulfonamides may be prescribed in age-appropriate doses if infection is a concern.

The goal of repositioning nasal bones is not only to improve the cosmetic appearance but also to restore physiological functions. This includes re-establishing normal nasal airflow patterns (inhalation and exhalation), which ensures proper fluctuations in air pressure within the nose and paranasal sinuses, as well as in other parts of the respiratory tract. Therefore, the main attention during repositioning is paid to restoring the usual configuration of the nasal cavity, modeling both its lower and upper parts. This allows the airstream during breathing to rise and follow the usual arcuate route, reaching the olfactory cleft during forced inhalation, which can help restore olfactory function.

Post-traumatic damage within the nasal cavity can sometimes lead to scar adhesions (synechiae) between its parts or the replacement of normal tissues (mucous membrane, septum, and concha) with massive, thick scars that disrupt respiratory and olfactory functions. To prevent cicatricial adhesions after nasal injury, plates or tubes made of various materials (e.g., X-ray film, rubber, Teflon, silicone) are sometimes inserted into the nose after reduction to keep mucosal surfaces separated during healing. Necrosis of the septal cartilage due to severe trauma or untreated hematoma/abscess can result in a saddle nose deformity.

Paranasal Sinus Trauma

Etiology and Associated Injuries

Injuries to the paranasal sinuses are frequently associated with injuries to the nose and other facial structures. Common causes include transport accidents (motor vehicle collisions), assaults, falls, and various emergencies. The frontal and ethmoid sinuses are most often affected, commonly with concomitant damage to surrounding organs and tissues such as the eyes, lacrimal sac, nasolacrimal canal, and potentially the contents of the cranial cavity (brain and meninges). If the maxillary sinus is injured, tissues of the cheeks, the oral cavity, and the dentition (teeth) are also often damaged.

Symptoms of Paranasal Sinus Trauma

The symptoms of paranasal sinus injury depend on the specific sinus(es) involved and the extent of combined damage to neighboring organs. Key signs and symptoms include:

- Headache: An almost constant symptom.

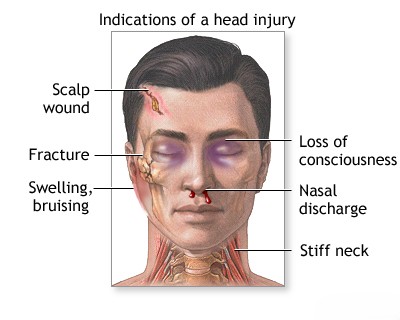

- Signs of Brain Injury: Prolonged unconsciousness often indicates a concussion or contusion of the brain with possible hemorrhage into the cranial cavity. Vomiting, dizziness, papilledema (congestion in the fundus of the eye), changes in pulse rate, fever, and sometimes memory and psychiatric disorders can occur with injuries to the skull bones and brain.

- Epistaxis: Bleeding from the nose and often from the wound itself is almost always present.

- Subcutaneous Emphysema: With closed injuries to the paranasal sinuses, air can escape into the subcutaneous tissues if the sinus wall and overlying mucosa are breached. This is determined by a crunching sensation (crepitus) during palpation of the swollen skin area.

- Pneumocephalus (Pneumatocele): If the walls separating the sinuses from the cranial cavity are damaged (e.g., posterior wall of frontal sinus, roof of ethmoid/sphenoid), an intracranial air collection can form. Air penetration into the cranial cavity occurs due to the pressure difference between intracranial and atmospheric pressure.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Liquorrhea (Rhinorrhea): An important symptom indicating a breach of the skull base and dura mater is the leakage of CSF from the nose. This often originates from the area of the cribriform plate (ethmoid roof) or the frontal sinus.

- Sphenoid Sinus Injury: Symptoms are determined by the state of neighboring organs. Bleeding from the nose is possible with damage to the cavernous sinus. Blindness and paralysis of oculomotor nerves (CN III, IV, VI) may occur. Rupture of the internal carotid artery with hemorrhage into the cavernous sinus can sometimes lead to pulsating exophthalmos (bulging of the eyeball synchronous with the pulse).

- Retained Foreign Bodies: With certain injuries (e.g., falling from a height onto a sharp object), foreign bodies may become lodged in the sinuses and remain unrecognized for a long time.

- Orbital Complications: Damage to the paranasal sinuses is fraught with the risk of orbital complications (see specific section on rhinogenic orbital complications).

- Lacrimation (Epiphora): Can result from damage to the nasolacrimal canal.

- Impaired Sense of Smell (Respiratory Hyposmia or Anosmia): Due to direct trauma or obstruction.

Diagnosis of Paranasal Sinus Trauma

Establishing the diagnosis of paranasal sinus trauma involves:

- Understanding the Mechanism of Injury: This helps to classify the injury more accurately and identify potential patterns of damage.

- Clinical Examination: Look for deformation of the facial skeleton, bleeding from the nose, pain, difficulty in nasal breathing (less often anosmia), sometimes loss of consciousness, subcutaneous emphysema, and crepitus of bones. These signs can help recognize a combined fracture of the nasal bones and paranasal sinuses.

- Otorhinolaryngological Examination: Including anterior rhinoscopy and nasal endoscopy to assess the nasal cavity, septum, turbinates, and look for CSF leak or signs of sinus involvement.

- Imaging Studies:

- X-ray Examination: Can provide initial assessment but may not fully delineate complex fractures.

- Computed Tomography (CT) of Facial Bones and Paranasal Sinuses: This is the gold standard for diagnosing sinus fractures, determining their extent, identifying associated injuries (e.g., orbital, skull base), and planning treatment. Both bone and soft tissue windows are important.

- MRI: May be useful if soft tissue injury, intracranial complications, or optic nerve damage is suspected.

Complications of Nasal and Paranasal Sinus Trauma

Traumatic injuries to the nose and paranasal sinuses can lead to a range of early and late complications.

Early Complications

- Epistaxis (Nosebleed): Common and can sometimes be severe.

- Septal Hematoma/Abscess: Collection of blood or pus under the septal perichondrium, risking cartilage necrosis.

- CSF Rhinorrhea (Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak): Indicates skull base fracture and dural tear, posing a risk of meningitis.

- Orbital Complications: Orbital hematoma, entrapment of extraocular muscles, optic nerve injury, orbital emphysema.

- Soft Tissue Infections: Cellulitis or abscess formation.

- Airway Obstruction: From severe swelling, hematoma, or displaced structures.

Late Complications

- Facial Deformity: Insufficient connection and fusion of fractured tissues can lead to lasting deformation of the face. This can be avoided by early and accurate reduction and fixation of fragments. Late complications include plate-shaped facial deformity (dished-in midface), abnormal fusion of fragments (malunion), and impaired growth and development of facial bones in children.

- Dental Issues: Delayed eruption of teeth or incorrect formation can occur, especially with maxillary trauma in children, requiring joint management with a dentist.

- Diplopia (Double Vision): Persistent double vision due to orbital floor/wall fractures with muscle entrapment or nerve injury.

- Saddle Nose Deformity: Collapse of the nasal bridge due to loss of septal support.

- Traumatic Hypertelorism: Increased distance between the orbits.

- Chronic Sinusitis: Due to obstruction of sinus drainage pathways by scarring or deformity.

- Mucocele Formation.

- Meningitis (Delayed Onset): Can result from an untreated or unrecognized CSF leak.

- Post-Traumatic Headache: Persistent headaches.

- Epilepsy: Can occur as a late sequela of severe head trauma involving intracranial injury.

- Persistent Loss of Smell (Anosmia): Especially with injury to the cribriform plate or olfactory pathways.

- Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction: Leading to chronic epiphora.

- Chronic Pain Syndromes.

Timely and effective management of trauma to the paranasal sinuses and nasal structures significantly reduces the number of complications associated with fractures of the facial skeleton and skull base.

Differential Diagnosis of Facial Trauma Symptoms

When evaluating a patient after facial trauma, it's important to consider the full spectrum of potential injuries:

| Symptom/Sign | Possible Traumatic Injuries | Other Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Nasal Deformity/Swelling | Nasal bone fracture, septal fracture/dislocation, septal hematoma, soft tissue contusion. | Pre-existing deformity. |

| Epistaxis | Mucosal laceration, nasal/septal fracture, sinus fracture, skull base fracture (anterior cranial fossa). | Underlying bleeding disorder, hypertension (less likely acute cause). |

| Periorbital Ecchymosis ("Raccoon Eyes") | Direct orbital trauma, nasal fracture, Le Fort II/III fractures, anterior skull base fracture. | Coagulopathy. |

| Clear Nasal Discharge (after trauma) | CSF Rhinorrhea (skull base fracture with dural tear). | Allergic rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis (less likely immediately post-trauma unless pre-existing). |

| Diplopia, Restricted Eye Movements, Enophthalmos/Exophthalmos | Orbital wall fracture (blowout fracture) with muscle entrapment, orbital hematoma, optic nerve injury, cranial nerve palsy (III, IV, VI). | Pre-existing strabismus, thyroid eye disease. |

| Facial Numbness/Paresthesia | Infraorbital nerve injury (maxillary fracture), supraorbital nerve injury (frontal bone/sinus fracture), trigeminal nerve branch injury. | Pre-existing neuropathy. |

| Malocclusion (Bite Abnormality) | Mandibular fracture, maxillary fracture (Le Fort types), alveolar ridge fracture. | Pre-existing dental issues. |

| Anosmia/Hyposmia | Cribriform plate fracture, olfactory nerve injury, severe nasal obstruction from swelling/hematoma. | Pre-existing olfactory dysfunction. |

Prevention and When to Seek Specialist Care

Prevention involves safety measures to avoid facial trauma (e.g., seatbelts, helmets during sports, workplace safety).

Urgent medical evaluation by an ENT specialist, maxillofacial surgeon, or at an emergency department is crucial after any significant nasal or facial trauma, especially if there is:

- Obvious nasal or facial deformity.

- Persistent or severe epistaxis.

- Difficulty breathing through the nose.

- Clear watery discharge from the nose (suspicion of CSF leak).

- Changes in vision, double vision, or restricted eye movements.

- Facial numbness.

- Changes in bite (malocclusion).

- Loss of consciousness or signs of head injury.

Early and accurate diagnosis and management by specialists are key to restoring function, minimizing cosmetic deformity, and preventing long-term complications from nasal and paranasal sinus injuries.

References

- Hollier L, Grantcharova EP, Kattash M. Facial gunshot wounds: a 4-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001 Mar;59(3):277-82. (Context for severe trauma)

- Kucik CJ, Clenney T, Phelan K. Management of acute nasal fractures. Am Fam Physician. 2004 Oct 1;70(7):1315-20.

- Rohrich RJ, Adams WP Jr. Nasal fracture management: minimizing secondary nasal deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 Aug;106(2):256-63.

- Staffel JG. Optimizing treatment of nasal fractures. Laryngoscope. 2002 Sep;112(9):1709-19.

- Strong EB. Evaluation and Treatment of Nasal Fractures. In: Bailey BJ, Johnson JT, Newlands SD, eds. Head & Neck Surgery—Otolaryngology. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:chap 68.

- Yaremchuk MJ. Maxillofacial trauma. In: Thorne CH, ed. Grabb and Smith's Plastic Surgery. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:chap 33.

- Mondin V, Rinaldo A, Ferlito A. Management of nasal bone fractures. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005 May-Jun;26(3):181-5.

- Zachariades N, Papavassiliou D, Koumoura F. Fractures of the facial skeleton in children. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1990 Dec;18(8):338-41.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis