Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Understanding Ozena (Primary Atrophic Rhinitis)

- Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations of Ozena

- Diagnosis of Ozena

- Treatment Strategies for Ozena

- Ozena and Associated Conditions

- Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Rhinitis with Crusting and Odor

- Complications and Prognosis

- When to Consult an ENT Specialist

- References

Understanding Ozena (Primary Atrophic Rhinitis)

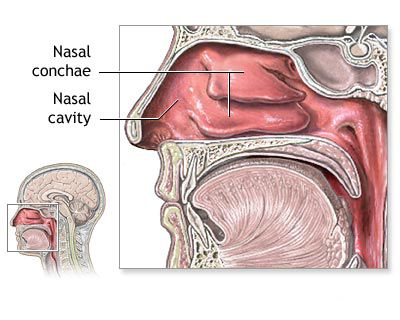

Ozena, also known as primary atrophic rhinitis, is a chronic and debilitating nasal disease characterized by progressive atrophy (shrinkage and thinning) of the nasal mucosa, submucosa, and underlying turbinate bones. This leads to abnormally widened nasal cavities, the formation of thick, dry, foul-smelling crusts, and a paradoxical sensation of nasal obstruction despite the increased airway space.

Ozena is more commonly observed in females, often beginning around puberty, and its symptoms may sometimes diminish or disappear in adulthood. The condition can significantly impact a patient's quality of life due to its persistent symptoms and social stigma associated with the offensive odor.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Despite numerous theories and extensive research, the precise etiology of ozena remains largely unclear to this day. It is likely multifactorial, with several contributing elements proposed:

- Genetic Factors: A familial predisposition has been suggested, as ozena can sometimes affect multiple family members.

- Infectious Agents: Chronic bacterial infection is strongly implicated, particularly with specific organisms such as *Klebsiella ozaenae*. Other bacteria like *Proteus vulgaris*, Diphtheroids, and *Bacillus mucosus* have also been isolated. These bacteria may contribute to the atrophy and the characteristic foul odor through their metabolic byproducts.

- Nutritional Deficiencies: Deficiencies in vitamins (especially Vitamin A and D) and iron have been considered as potential contributing factors.

- Endocrine Imbalances: The predilection for females and onset around puberty suggests a possible hormonal influence.

- Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction: Imbalance in sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the nasal mucosa might play a role.

- Autoimmune Processes: Some theories suggest an autoimmune basis for the mucosal destruction.

- Environmental Conditions: Prolonged exposure to dry, dusty climates or irritants may exacerbate the condition, although it's not considered a primary cause.

Ozena typically begins insidiously, sometimes around the age of 8 years or during puberty.

Morphological Changes

The pathological changes in ozena are distinctive and progressive:

- Mucosal Atrophy: The normal ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium of the nasal mucosa undergoes metaplasia, transforming into stratified squamous epithelium, which may become keratinized and is subsequently rejected (sloughed off).

- Glandular Atrophy: There is a marked decrease in the number and activity of seromucinous glands within the nasal mucosa, leading to reduced mucus production and nasal dryness.

- Vascular Changes: Endarteritis obliterans (inflammation and obliteration of small arteries) can contribute to reduced blood supply and tissue atrophy.

- Bone Resorption: The underlying bony skeleton of the nasal turbinates (especially the inferior and middle turbinates) undergoes resorption and atrophy, leading to abnormally wide nasal passages.

- Loss of Olfactory Epithelium: Atrophy extends to the olfactory region, leading to impaired sense of smell.

Symptoms and Clinical Manifestations of Ozena

Ozena presents with a characteristic triad of symptoms:

- Fetid Odor (Cacosmia): A hallmark of ozena is an offensive, putrid odor emanating from the nose, which is often very noticeable to others but typically not perceived by the patient themselves. This "mercy anosmia" is due to atrophy of the olfactory nerve endings.

- Nasal Crusting: Formation of thick, dry, tenacious crusts that are often greenish-gray or blackish. These crusts can be extensive, sometimes forming a cast of the nasal cavity, and are difficult to remove. The underlying mucosa is often friable and may bleed when crusts are dislodged.

- Nasal Cavity Widening due to Atrophy: Progressive atrophy of the nasal mucosa and turbinate bones leads to abnormally roomy nasal passages.

Other common symptoms and findings include:

- Paradoxical Nasal Obstruction: Despite the wide nasal cavity, patients often complain of nasal blockage or difficulty breathing through the nose. This is thought to be due to the loss of normal airflow sensation and excessive dryness.

- Anosmia or Severe Hyposmia: Impaired or complete absence of the sense of smell due to damage to the olfactory epithelium and nerve endings.

- Nasal Dryness and Throat Dryness (Pharyngitis Sicca): Due to reduced mucus production and altered airflow.

- Epistaxis (Nosebleeds): From dry, atrophic, and crusted mucosa.

- Headache or Facial Discomfort.

- Extension to Lower Airways: The atrophic process can sometimes extend downwards, leading to atrophic pharyngitis, laryngitis sicca (dry larynx), and tracheobronchitis, with associated hoarseness or cough.

On rhinoscopy, the nasal cavities appear excessively patent. The nasal turbinates are atrophic and small. The mucosa under the crusts is typically sharply atrophic, velvety-red, and may bleed easily. Sometimes, the bony skeleton of the turbinates is visible. Similar, though usually less severe, atrophic changes with crusting may be observed in the posterior nasal cavity and nasopharynx. The posterior pharyngeal wall may also appear dry, shiny (as if covered with varnish), and crusted.

Diagnosis of Ozena

The diagnosis of ozena is primarily based on the characteristic clinical triad of foul odor, crusting, and atrophic changes within a widened nasal cavity. Key diagnostic steps include:

- Clinical History: Detailed history of symptoms, including onset, duration, nature of nasal discharge and odor, associated symptoms like nasal obstruction or dryness, and family history.

- Physical Examination:

- Anterior and Posterior Rhinoscopy/Nasal Endoscopy: Essential for visualizing the atrophic mucosa, widened nasal passages, shrunken turbinates, and the presence of characteristic crusts. The color and consistency of the crusts and underlying mucosa are noted.

- Microbiological Studies: Swabs from nasal crusts or secretions may be sent for culture to identify predominant bacterial flora, particularly *Klebsiella ozaenae* or other implicated organisms.

- Imaging:

- CT Scan of the Paranasal Sinuses: Can demonstrate the extent of mucosal atrophy, turbinate bone resorption, widening of the nasal fossae, and may show associated sinus opacification or mucosal thickening (often due to retained secretions or secondary infection).

- Biopsy (Rarely needed for typical ozena): In cases with atypical features or to rule out other conditions like granulomatous diseases or malignancy, a biopsy of the nasal mucosa may be performed. Histopathology will show squamous metaplasia, atrophy of glands and ciliated epithelium, and chronic inflammatory infiltrate.

- Olfactory Testing: To quantify the degree of hyposmia or anosmia.

Secondary atrophic rhinitis, which can result from previous aggressive nasal surgery, chronic granulomatous diseases (e.g., syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy), chronic sinusitis, or prolonged exposure to irritants, must be differentiated from primary atrophic rhinitis (ozena).

Treatment Strategies for Ozena

The treatment of ozena is challenging and primarily aims at symptomatic relief, as there is no definitive cure for the underlying atrophic process. Exceptional perseverance from both the physician and the patient is required, involving a combination of local and sometimes general therapeutic measures.

Local Conservative Treatment (Mainstay)

The cornerstone of ozena management is meticulous and regular nasal hygiene to remove crusts, moisturize the mucosa, reduce odor, and control secondary infection:

- Nasal Irrigation and Douching: Frequent (often daily or twice daily) irrigation of the nasal cavities with large volumes of warm saline or alkaline solutions (e.g., 1% sodium bicarbonate solution, sometimes with glycerin added for moisturization) is essential. This helps to loosen and remove tenacious crusts and debris. A nasal douche can or specialized irrigation bottle (e.g., NeilMed Sinus Rinse) is used. It is important **not to use a syringe** for irrigation with forceful pressure, as this can promote the penetration of fluid into the Eustachian tube openings, potentially causing otitis media. During irrigation, the head should be tilted slightly forward, and the patient should breathe through the mouth, trying not to swallow the water. The solution typically flows out of the other nostril. After rinsing, the patient should gently blow each nostril separately. Dry, adherent crusts should be softened first (e.g., with oil or ointment application) before attempting irrigation.

- Topical Medications and Lubricants:

- Moisturizers and Emollients: Application of sterile vaseline, paraffin oil, or bland emollient ointments (e.g., peach oil, apricot oil) to the nasal mucosa for 1-2 hours (e.g., using tampons soaked in the oil) helps to soften crusts and keep the mucosa hydrated.

- Iodine-Glycerine (Lugol's Solution): Daily lubrication of the nasal mucosa with iodine-glycerine has been traditionally used for its mild antiseptic properties and to potentially stimulate remaining glandular function.

- Antibiotics: Topical antibiotic solutions or ointments (e.g., gentamicin, bacitracin) may be used during periods of acute infection or to reduce bacterial load, sometimes mixed with glucose or glycerin. Systemic antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin, rifampicin) may be prescribed for longer durations based on culture results, particularly targeting *K. ozaenae*.

- Other Historical Topical Agents: Mentions of bee chalk (propolis) have appeared in some traditional remedies.

- Alkaline Inhalations: Steam inhalations with alkaline solutions can also help moisturize and loosen crusts.

Systemic and Supportive Therapies

- Nutritional Supplementation: Addressing potential deficiencies with Vitamin A, Vitamin D, iron, and zinc.

- Vasodilators: Some systemic vasodilators (e.g., nicotinic acid) have been tried to improve mucosal blood flow, but efficacy is uncertain.

- Immunomodulators/Stimulants (Historical/Supportive):

- Autohemotherapy (injecting the patient's own blood intramuscularly).

- Blood transfusion (in severe cases with anemia or debilitation).

- Protein therapy and vaccine therapy (e.g., staphylococcal vaccines if this organism is predominant).

- Injections of aloe extract or cocarboxylase.

Surgical Interventions (Palliative)

Surgical procedures for ozena are palliative, aiming to reduce the size of the excessively patent nasal cavities, thereby decreasing dryness, crust formation, and odor by altering airflow dynamics and increasing mucosal moisture. They do not reverse the atrophic process. Techniques include:

- Young's Operation (Partial or Complete Nostril Closure): One or both nostrils are surgically closed or significantly narrowed by creating mucosal flaps. This reduces airflow, allowing the mucosa to rest and potentially regenerate some function, and decreases crusting and odor. It can be temporary or permanent.

- Submucosal Implants: Various materials (e.g., autologous cartilage or bone, Teflon, silicone, hydroxyapatite) are implanted beneath the septal or lateral nasal wall mucosa to narrow the nasal passages.

- Medial Displacement of Lateral Nasal Wall or Turbinate Augmentation.

- Parotid Duct Transposition (Wittmaack's operation - historical/rare): The parotid duct is rerouted to empty saliva into the maxillary sinus or nasal cavity to provide moisture. This procedure has significant potential complications and is rarely performed.

Surgery is typically reserved for severe cases unresponsive to intensive conservative management.

Ozena and Associated Conditions

In adults, what appears to be ozena can sometimes mask an underlying chronic purulent process of the paranasal sinuses, particularly involving the ethmoid labyrinth and sphenoid sinus. In such cases, identifying and treating the source of suppuration is crucial, as this can be difficult.

Reflex Neuroses and Menstrual Disorders (Historical Context)

Historically, various "reflex neuroses" (e.g., headache, neuralgia, asthma, cough, epileptoid seizures) were sometimes attributed to nasal pathology. The modern perspective is that while pathological changes in the nose (like those in ozena or severe obstruction) should be addressed if they cause significant symptoms (e.g., breathing difficulty), it's not guaranteed that treating the nasal condition will resolve unrelated "nervous suffering." Surgery to eliminate anatomical causes of breathing difficulties has the best chance of success for respiratory symptoms, and reflex disorders may decrease thereafter.

Opinions have also varied on the impact of nasal treatment on menstrual disorders. There are anecdotal historical reports where treatments like cauterizing specific points in the nose (e.g., anterior end of the inferior concha with cocaine) temporarily or for a long time relieved menstrual pain or cramps (dysmenorrhea). While the scientific basis for such connections is not well-established, such treatments were sometimes attempted empirically in the past if no other cause for dysmenorrhea was found and nasal pathology coexisted.

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Rhinitis with Crusting and Odor

Ozena needs to be differentiated from other conditions causing similar symptoms:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Ozena (Primary Atrophic Rhinitis) | Progressive atrophy of mucosa and bone, very wide nasal passages, severe crusting, characteristic fetid odor (often anosmia in patient), more common in females, onset often around puberty. |

| Secondary Atrophic Rhinitis | History of previous aggressive nasal surgery (e.g., turbinectomy causing "empty nose syndrome"), chronic granulomatous disease (syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy, sarcoidosis), sinonasal tumors with bone destruction, long-term exposure to industrial irritants, or radiation therapy. Atrophy and crusting present, odor may or may not be as fetid as in ozena. |

| Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Crusting | Persistent inflammation, purulent discharge, polyps may be present. Crusting can occur, but typically without the severe atrophy and extreme widening of nasal passages seen in ozena. Odor may be present but usually less offensive than ozena. CT shows sinus disease. |

| Rhinitis Sicca Anterior | Dryness and crusting localized to the anterior nasal cavity (septum and vestibule), often due to dry environment or nose picking. No generalized atrophy or fetid odor. |

| Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA/Wegener's) | Nasal crusting, bloody discharge, septal perforation, saddle nose deformity. Systemic symptoms (renal, pulmonary involvement). ANCA positive. Biopsy shows necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis. |

| Nasal Foreign Body (long-standing) or Rhinolith | Usually unilateral, foul purulent discharge, obstruction. Object or stone visible on examination/imaging. |

Complications and Prognosis

If left unmanaged, ozena can lead to:

- Persistent and severe anosmia.

- Chronic pharyngitis sicca and laryngitis sicca.

- Recurrent epistaxis.

- Maggot infestation (myiasis) in endemic areas due to the foul odor.

- Social isolation and psychological distress due to the offensive smell.

- Hearing impairment due to Eustachian tube dysfunction from nasopharyngeal involvement.

The prognosis for ozena in terms of complete cure of the atrophic process is poor. However, diligent and lifelong conservative treatment can significantly alleviate symptoms, control odor and crusting, and improve the patient's quality of life. Spontaneous improvement or resolution sometimes occurs in adulthood, but this is not predictable.

When to Consult an ENT Specialist

Individuals experiencing symptoms suggestive of ozena or any form of chronic atrophic rhinitis should consult an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist. Key indications include:

- Persistent, foul nasal odor noticeable to others.

- Chronic, thick nasal crusting.

- Progressive nasal dryness and sensation of obstruction.

- Significant loss of sense of smell.

- Recurrent nosebleeds associated with nasal dryness.

An ENT specialist can confirm the diagnosis, rule out other conditions, and establish a long-term management plan involving regular nasal care and monitoring.

References

- Sheehy JL. Ozena: a disappearing disease. Laryngoscope. 1980;90(9):1473-1477.

- Bunnag C, Jareoncharsri P, Tansuriyawong P, Bhothisuwan W, Chantarakul N. Characteristics of atrophic rhinitis in Thai patients at the Siriraj Hospital. Rhinology. 1999 Mar;37(1):29-32.

- Chand MS, Macarthur AM. Primary atrophic rhinitis: a summary of results of a survey in Northern Nigeria. J Laryngol Otol. 1977;91(10):861-868.

- Hitanay M, Kumar B, Singh NK. Primary atrophic rhinitis: a clinical profile. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 Jul;65(Suppl 1):149-53.

- Moore EJ, Kern EB. Atrophic rhinitis: a review of 242 cases. Am J Rhinol. 2001 Nov-Dec;15(6):355-61.

- Sinha SN, Sardana DS, Rajvanshi VS. A 10-year study of atrophic rhinitis with special reference to Klebsiella ozaenae. J Laryngol Otol. 1977 Jul;91(7):591-600.

- El-Silimy O. Young's operation for atrophic rhinitis (ozena). J Laryngol Otol. 1983 Jan;97(1):29-34.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis