Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Understanding Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

- Diagnosis and Symptoms of Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

- Comprehensive Treatment Strategies for Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

- Perfume (Cosmetic) Rhinitis: An Overview

- Understanding Vasomotor Rhinitis (Non-Allergic Rhinitis)

- Management Approaches for Vasomotor Rhinitis

- Differential Diagnosis: Allergic Rhinitis vs. Vasomotor Rhinitis

- When to Consult an ENT Specialist

- References

Understanding Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

In children, allergic rhinitis and sinusitis frequently present together and may be complicated by a vasomotor (non-allergic) component. Treating allergic rhinitis and sinusitis as isolated conditions is somewhat reductive, as any allergic reaction impacting the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses represents a localized expression of systemic hypersensitivity. Current medical understanding underscores that effective management of upper respiratory tract inflammatory diseases, especially in pediatric patients, must consider the individual's underlying allergic predisposition [1].

The onset of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis often occurs in early childhood. This is influenced by various factors including the maturation of the child's immune system, frequency of acute respiratory infections, genetic predispositions (heredity), hormonal fluctuations, and diverse environmental exposures. Allergens can enter a child's system through multiple pathways: transplacentally (from mother to fetus during pregnancy), orally (via ingested food), through the respiratory tract (by inhalation of airborne particles), or via direct skin contact.

Allergens and Sensitization Pathways

Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis in children can be initiated by a broad spectrum of exogenous (external) allergens, including:

- Household Allergens: Common examples include dust mite feces, dander from pets (such as cats, dogs, and rodents), cockroach residues, and various mold spores.

- Food Allergens: Frequently implicated foods are cow's milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, wheat, fish, and shellfish, though many other foods can also act as allergens.

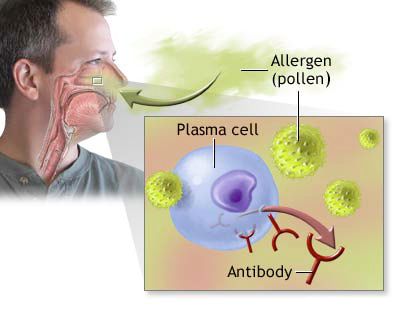

- Pollen Allergens: Airborne pollens from trees, grasses, and weeds are notorious for causing seasonal allergic rhinitis (hay fever).

- Medicinal Allergens: Certain medications, including some antibiotics (e.g., penicillin), sulfonamides, salicylates (like aspirin), and bromides, have the potential to induce allergic reactions.

- Bacterial and Viral Components: While primarily infectious agents, specific proteins or components of bacteria and viruses can occasionally trigger allergic-type responses in sensitized individuals.

Endogenous (internal) factors, such as pre-existing inflammation from other causes, can also modulate or exacerbate allergic responses. Allergic reactions are broadly classified based on their timing: immediate reactions occur within minutes of allergen exposure, whereas delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions may develop hours or even days later.

Specific types of allergies, such as serum (vaccinal) allergies, fungal allergies (e.g., to molds like Aspergillus or Alternaria), and helminth (parasitic worm) induced allergies, are also significant considerations in pediatric populations. Food-induced allergic rhinitis and sinusitis can arise from repeated or excessive consumption of particular allergenic foods. It is common for children to exhibit polyallergy, meaning they are sensitized to multiple different allergens. During the first year of life, allergic manifestations are predominantly cutaneous (e.g., atopic dermatitis/eczema) or gastrointestinal. However, by the age of 2-3 years, the upper respiratory tract frequently becomes the primary site for allergic symptoms.

Diagnostic Approaches for Allergy

A comprehensive allergological evaluation begins with meticulous history-taking. This includes a detailed family history, noting any allergic diseases (asthma, eczema, rhinitis) in parents or other close relatives. The patient's personal history should cover any known allergic reactions to specific triggers like animal contact, dust exposure, bedding materials, previous immunizations, use of therapeutic serums, past blood or plasma transfusions, and a record of any prior allergic diseases or acute reactions.

When clinically indicated, allergy testing is pursued. Skin-prick tests (SPTs) or specific IgE (sIgE) blood tests (e.g., RAST or ImmunoCAP) are commonly employed to identify sensitization to prevalent inhalant allergens (pollens, dust mites, molds, animal dander) and food allergens. In cases where bacterial sensitization is suspected as a contributing factor, tests using bacterial allergens (e.g., Staphylococcal, Streptococcal lysates) might be considered, though their clinical utility is debated. While skin testing, if performed and interpreted correctly by a trained professional, can provide valuable information, it is not invariably definitive. Skin reactivity does not always correlate perfectly with the severity or presence of respiratory symptoms, and false positives or negatives can occur.

The presence of eosinophilia (an increased number of eosinophils, a specific type of white blood cell) in nasal secretions or sinus aspirates is suggestive of an allergic inflammatory process, although its presence can be variable. Tissue eosinophilia, identified in biopsy specimens from the nasal mucosa, is regarded as a more robust and pathognomonic indicator of allergic inflammation. Nevertheless, these cytological tests are most valuable when interpreted within the context of a comprehensive clinical evaluation, not as standalone diagnostic markers, and their findings can fluctuate based on recent exposures or treatment.

Peripheral blood eosinophilia (typically defined as an absolute eosinophil count greater than 5-6% of the total white blood cell count or >500 cells/µL) is a well-recognized, albeit non-specific, indicator of allergic conditions in children. However, since elevated blood eosinophils can also be associated with other conditions such as helminth (parasitic worm) infections, certain skin diseases (e.g., psoriasis, pemphigus), and some chronic myeloproliferative disorders, further diagnostic investigations (e.g., stool examination for ova and parasites) are often warranted to rule out these alternative causes. In complex cases, more extensive testing, potentially including controlled allergen provocation tests (nasal, bronchial, or oral challenges performed under strict medical supervision), may be necessary.

For identifying food allergies and establishing a clear link with specific food items (in conjunction with formal allergy testing), maintaining a detailed food and symptom diary can be extremely useful. This practice involves meticulous recording of all foods and beverages consumed daily, alongside any observed allergic reactions or symptoms and their timing. If the exclusion of a suspected food from the diet leads to a resolution or significant improvement of symptoms, and subsequent reintroduction of that food (preferably under medical guidance, especially if severe reactions are a concern) causes the symptoms to reappear, this provides strong evidence supporting that food as a causative allergen.

Diagnosis and Symptoms of Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

Clinical Manifestations and Observations

The allergic manifestation of rhinitis and sinusitis is frequently characterized by a chronic or recurrent course, often with seasonal exacerbations (e.g., during spring pollen season for hay fever) or perennial symptoms (due to indoor allergens like dust mites or molds). Symptom-free or reduced-symptom periods (remissions) may occur, particularly in winter for those with seasonal pollen allergies. Key clinical symptoms include:

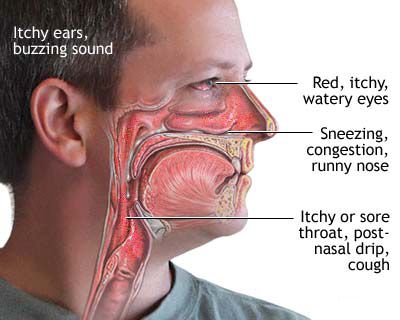

- Nasal Congestion: A persistent feeling of a stuffy, blocked, or obstructed nose.

- Rhinorrhea: Typically profuse, clear, and watery nasal discharge (runny nose).

- Sneezing: Often occurring in paroxysms (bouts of multiple, repetitive sneezes).

- Nasal Pruritus (Itching): An itchy sensation in the nose, frequently accompanied by itching of the soft palate, throat, and eyes.

- Post-Nasal Drip: The sensation of mucus accumulating and dripping down the back of the throat, often leading to throat clearing or a cough.

- Ocular Symptoms (Allergic Conjunctivitis): Commonly co-occurs, presenting as red, itchy, watery, and sometimes swollen eyes.

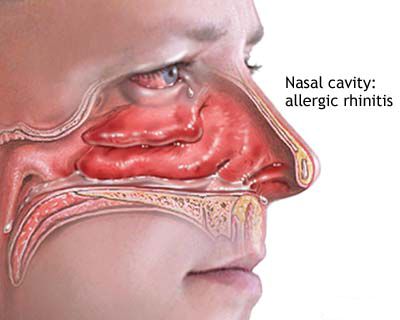

Upon physical examination of the nasal passages (rhinoscopy), an ENT specialist often observes pronounced swelling (edema) of the nasal mucous membrane. The mucosa may appear pale, boggy, or have a characteristic bluish or violaceous hue due to chronic venous engorgement. Whitish spots or a cobblestone appearance of the pharyngeal mucosa may also be noted. The nasal turbinates (bony structures inside the nose covered with erectile mucosa) typically appear swollen and pale. In long-standing or severe cases, nasal polyposis (the development of benign, grape-like growths called polyps from the nasal or sinus mucosa) can occur, further contributing to obstruction. Due to the intense nasal itching, children with allergic rhinitis often habitually rub the tip of their nose upwards with the palm of their hand. This characteristic gesture is known as the "allergic salute" and, over time, can lead to the formation of a transverse nasal crease across the lower bridge of the nose.

Radiological findings, such as X-rays or CT scans of the sinuses in allergic rhinosinusitis, can be dynamic and may show parietal (mucosal) thickening within the paranasal sinuses, fluid levels, or complete opacification, indicating the extent of the inflammatory process. A crucial diagnostic clue is often the lack of response or transient improvement with conventional treatments for common viral colds or presumed bacterial infections, contrasted with a noticeable and sustained positive response to appropriate antiallergic therapy (e.g., antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids).

Associated Allergic Conditions and Morphological Changes

Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis frequently form part of the "allergic march," often coexisting or being temporally associated with other allergic diseases and manifestations. These include:

- Bronchial asthma

- Atopic dermatitis (eczema)

- Psoriasis (which can have allergic triggers or co-occur with atopic conditions)

- Urticaria (hives) and Angioedema (deeper tissue swelling)

- Migraine headaches (which can be triggered by allergens or histamine release in some susceptible individuals)

- Pollinosis (seasonal allergic rhinitis or hay fever specifically due to pollens)

- Food allergies

A definitive diagnosis confirming the allergic nature of the rhino-sinus inflammatory process relies on a holistic and comprehensive assessment. This integrates the detailed clinical history and symptom pattern, findings from a thorough allergological investigation (including allergy testing), and specific laryngological (ENT) examinations, such as nasal endoscopy.

Microscopically, the morphological changes in the nasal and sinus tissues affected by allergic rhinitis and sinusitis are characterized by a significant infiltration of inflammatory cells, predominantly eosinophils and mononuclear cells (lymphocytes, macrophages). The mucosal lining often exhibits thickening (hyperplasia) and may show a tendency towards polypoid degeneration (formation of polyps). Edema (swelling) of the submucosal tissue is prominent. There is often proliferation of connective tissue elements, including fibroblasts, leading to fibrosis in chronic cases. Glands within the mucosa may appear swollen and compressed. Significant alterations occur in the vascular bed, with vasodilation and increased permeability. Changes are also observed in the extracellular matrix, affecting the structure of collagen fibers and the composition of the ground substance. Thickening of the basement membrane underlying the epithelium is another common histological feature.

Comprehensive Treatment Strategies for Allergic Rhinitis and Sinusitis

The effective management of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis is multifaceted, focusing on several key strategic pillars. These include the accurate identification and subsequent elimination or minimization of exposure to causative allergen(s), the judicious use of pharmacotherapy to control symptoms and underlying inflammation, the implementation of allergen-specific desensitization (immunotherapy) in suitable candidates, and, where necessary, addressing any concomitant infections (e.g., through sanitation of chronic infection foci like adenoids or tonsils) or structural abnormalities.

Allergen Avoidance and Environmental Control Measures

Once specific allergens are identified through history and testing, the cornerstone of management is to reduce or eliminate exposure. Practical environmental control measures include:

- For Dust Mite Allergy: Encase pillows, mattresses, and box springs in allergen-impermeable covers. Wash all bedding (sheets, pillowcases, blankets) weekly in hot water (at least 130°F or 55°C). Reduce indoor humidity levels to below 50% using dehumidifiers or air conditioning. Remove carpets, upholstered furniture, heavy drapes, and clutter from the bedroom. Opt for hard flooring and wipeable surfaces.

- For Pollen Allergy: Keep windows and doors closed during high pollen seasons, especially during peak pollen times (typically morning and early evening). Use air conditioning in homes and cars, set to recirculate air. Shower and change clothes after spending extended time outdoors to remove pollen from skin and hair. Monitor local pollen counts and plan outdoor activities accordingly.

- For Pet Dander Allergy: Ideally, remove the pet from the home, or at a minimum, keep pets out of the allergic individual's bedroom and main living areas. Use HEPA (High-Efficiency Particulate Air) filters in central heating/cooling systems and standalone air purifiers. Regular grooming of pets (preferably by a non-allergic family member and outdoors) may help reduce dander levels. Wash hands after contact with pets.

- For Mold Allergy: Identify and repair all sources of water leaks or dampness promptly. Maintain low indoor humidity (below 50%). Ensure adequate ventilation in bathrooms, kitchens, and basements. Clean any visible mold from surfaces using appropriate cleaning solutions (e.g., diluted bleach). Avoid areas with high mold concentrations like damp basements or compost piles.

- For Food Allergens: Strict and complete avoidance of all identified allergenic foods is paramount. This requires careful reading of food labels, awareness of cross-contamination risks, and clear communication when dining out or when food is prepared by others.

In some severe and refractory cases, more significant lifestyle adjustments, such as relocating to a different climate or region (if environmental allergens are pervasive and unavoidable) or meticulously avoiding specific items like woolen clothing, fur products, plush toys, or strong-smelling flowers, might be necessary for symptom control.

Pharmacological Interventions (Pharmacotherapy)

A variety of medications are available to manage the symptoms and underlying inflammation of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis:

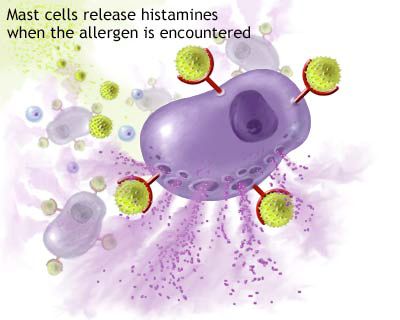

- Antihistamines: These drugs block the action of histamine, a key mediator of allergic symptoms. Second-generation oral antihistamines (e.g., loratadine, cetirizine, fexofenadine, desloratadine, levocetirizine) are generally preferred due to their non-sedating or less-sedating profiles. Intranasal antihistamine sprays (e.g., azelastine, olopatadine) offer rapid onset of action and are effective for nasal itching, sneezing, and rhinorrhea. First-generation antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine) are effective but can cause significant drowsiness and anticholinergic side effects.

- Intranasal Corticosteroids (INCS): These are widely regarded as the most effective first-line treatment for controlling the broad range of symptoms in persistent or moderate-to-severe allergic rhinitis. Examples include fluticasone propionate, fluticasone furoate, mometasone furoate, budesonide, ciclesonide, and triamcinolone acetonide. They work by reducing local inflammation, thereby alleviating nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, itching, and sneezing. Consistent daily use is crucial for optimal benefit, and maximal effect may take several days to weeks.

- Decongestants: Oral decongestants (e.g., pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine) can provide temporary relief from nasal stuffiness by causing vasoconstriction. Topical nasal decongestant sprays (e.g., oxymetazoline, xylometazoline, phenylephrine) offer rapid relief but should not be used for more than 3-5 consecutive days due to the risk of rebound congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa), a condition where congestion worsens with continued use.

- Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists (LTRAs): Drugs like montelukast block the action of leukotrienes, another group of inflammatory chemicals involved in allergic reactions. LTRAs can be particularly helpful for nasal congestion and are sometimes used as adjunctive therapy with antihistamines or INCS, especially in patients who also have concomitant asthma.

- Mast Cell Stabilizers: Cromolyn sodium, available as a nasal spray, works by preventing the release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators from mast cells. It is most effective when used prophylactically before anticipated allergen exposure and requires frequent dosing (3-4 times daily). It has an excellent safety profile.

- Saline Nasal Rinses/Sprays: Isotonic or hypertonic saline solutions, delivered via spray bottles, neti pots, or squeeze bottles, help to mechanically wash away allergens, mucus, and irritants from the nasal passages. This can provide symptomatic relief, improve ciliary function, and enhance the efficacy of other intranasal medications.

Systemic corticosteroids (administered orally or by injection) are generally reserved for short courses to manage severe, acute exacerbations or refractory symptoms due to the potential for significant side effects with prolonged use. Their routine or long-term topical application (e.g., hydrocortisone suspension) within the nasal cavity is not standard practice, may offer only temporary relief, and should be used with caution, particularly in children, due to risks of local and systemic absorption.

Allergen-Specific Immunotherapy (Desensitization)

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (SIT), also known as desensitization or "allergy shots/drops," is a disease-modifying treatment that can provide long-term relief and potentially alter the natural course of allergic disease. It involves the regular administration of gradually increasing doses of the specific allergen(s) to which the patient is clinically sensitized. The goal is to induce immune tolerance, making the immune system less reactive to those allergens over time. SIT is typically considered for patients with clearly identified allergen triggers, significant symptoms that are inadequately controlled by pharmacotherapy and avoidance measures, or those who experience undesirable side effects from medications. It is a long-term commitment, usually requiring treatment for 3 to 5 years. The two main routes of administration are:

- Subcutaneous Immunotherapy (SCIT): Involves regular injections administered in a medical setting.

- Sublingual Immunotherapy (SLIT): Involves daily administration of allergen extracts as tablets or drops placed under the tongue, which can often be self-administered at home after initial supervised doses.

Successful immunotherapy can lead to a reduction in symptoms, decreased medication needs, and an improved quality of life. However, comprehensive allergen identification can be challenging in individuals with polyallergy (sensitization to multiple allergens). While generally safe when administered correctly, immunotherapy itself carries a small risk of allergic reactions, ranging from local site reactions to, rarely, systemic anaphylaxis, necessitating careful patient selection and administration protocols.

Role of Surgical Interventions

Surgical intervention is generally reserved for cases of allergic rhinitis and sinusitis where medical management has failed to provide adequate symptom control, or when significant structural abnormalities are present that contribute to persistent symptoms or complications. Surgical procedures aim to improve nasal airflow, enhance sinus drainage, and facilitate the delivery of topical medications. Common procedures include:

- Turbinate Reduction (Turbinoplasty or Turbinectomy): To reduce the size of chronically enlarged (hypertrophied) nasal turbinates, thereby alleviating nasal obstruction. Various techniques can be employed, including electrocautery, radiofrequency ablation, microdebrider-assisted submucosal resection, or cryotherapy.

- Septoplasty (Correction of Deviated Nasal Septum): To straighten a deviated nasal septum that is causing significant nasal blockage or contributing to sinus issues.

- Polypectomy: The surgical removal of nasal polyps that obstruct the nasal passages or sinus ostia.

- Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS): A minimally invasive technique used to open blocked sinus drainage pathways, remove diseased tissue, and improve ventilation of the paranasal sinuses in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis refractory to medical therapy.

It is crucial to understand that surgery primarily addresses anatomical obstructions and improves drainage; it does not cure the underlying allergic diathesis. Therefore, continued medical management of the allergy (e.g., INCS, antihistamines, immunotherapy) is typically essential post-surgery to prevent recurrence of symptoms and inflammation. Modern surgical approaches emphasize gentle, tissue-sparing, minimally invasive techniques to optimize outcomes and minimize the risk of further sensitizing the nasal mucosa or causing complications like empty nose syndrome.

Interventions like reflexology and intranasal novocaine or lidocaine injections have been historically explored for their purported ability to modulate the nasal neural receptor apparatus and autonomic tone. However, their widespread efficacy and precise role in the modern management of allergic rhinitis require further validation through robust, well-designed clinical trials.

Perfume (Cosmetic) Rhinitis: An Overview

The pervasive use of aromatic additives and fragrances in a vast array of cosmetics, personal care products (e.g., soaps, shampoos, lotions), and household items (e.g., air fresheners, cleaning agents) has contributed to an increasing incidence of perfume-induced or cosmetic rhinitis. These chemical fragrances can act as potent irritants to the nasal mucosa or, in susceptible individuals, can function as specific allergens, triggering nasal symptoms characteristic of rhinitis. The chemical composition of these aromatic additives, often containing high lipid content (ranging from 20% to 80%), can influence their volatility, mucosal penetration, and potential toxicity. Prolonged or repeated exposure to such flavoring or fragrance agents can provoke symptoms such as a persistent runny nose (rhinorrhea), nasal congestion, sneezing, and sometimes associated skin inflammation (contact dermatitis) or eye irritation (conjunctivitis). The cornerstone of managing this type of rhinitis lies in the meticulous identification and subsequent avoidance of the specific offending product(s) or fragrance chemicals. This may require careful label reading (though full fragrance disclosure is not always mandatory) or a process of elimination.

Understanding Vasomotor Rhinitis (Non-Allergic Rhinitis)

Vasomotor rhinitis, often categorized under the broader term non-allergic rhinitis, is a chronic condition characterized by persistent nasal symptoms such as congestion, runny nose (rhinorrhea), and post-nasal drip. Crucially, these symptoms are not caused by an IgE-mediated allergic reaction (as in allergic rhinitis) or by an identifiable infection. It is believed to occur in individuals who have hyperreactive or hypersensitive nasal passages. Contemporary classifications recognize different forms, including a neurovegetative type (implying dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system supplying the nose) and, occasionally, mixed forms where non-allergic triggers coexist with some degree of allergic sensitization. Symptomatically, it can be further divided based on predominant features, such as a vasodilator type (where nasal congestion is the main complaint due to engorged blood vessels) or a hypersecretory type (where profuse watery rhinorrhea is dominant due to overactive nasal glands).

Common Triggers and Underlying Pathophysiology

Unlike allergic rhinitis, which is triggered by specific allergens, vasomotor rhinitis is initiated by a variety of non-allergic environmental or physiological factors. The precise pathophysiology is not fully elucidated but is thought to involve an imbalance in the autonomic nervous system's control over nasal blood vessels and glandular secretions, leading to an exaggerated or abnormal response to normally innocuous stimuli. Common triggers for vasomotor rhinitis include:

- Environmental Irritants: Exposure to strong odors (such as perfumes, colognes, smoke from tobacco or wood fires, chemical fumes from cleaning agents or industrial sources), air pollution (e.g., ozone, particulate matter), and dust.

- Changes in Weather and Atmospheric Conditions: Fluctuations in temperature (especially exposure to cold, dry air), changes in humidity levels, and shifts in barometric pressure.

- Hormonal Changes: Endocrine fluctuations associated with pregnancy ("rhinitis of pregnancy"), menstruation, puberty, or thyroid dysfunction (e.g., hypothyroidism) can trigger or worsen symptoms.

- Medications: Certain systemic medications are known to induce or exacerbate rhinitis symptoms. These include some antihypertensive drugs (e.g., beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, alpha-blockers), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs like aspirin and ibuprofen, especially in individuals with aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease), oral contraceptives, and psychotropic medications. Prolonged overuse of topical nasal decongestant sprays can lead to a rebound phenomenon known as rhinitis medicamentosa.

- Stress and Strong Emotions: Psychological stress and intense emotional states can influence autonomic nervous system activity and trigger nasal symptoms in susceptible individuals.

- Certain Foods and Beverages: Consumption of spicy foods (gustatory rhinitis), alcoholic beverages (especially red wine), or very hot foods/drinks can provoke nasal congestion and rhinorrhea in some people.

The clinical presentation of vasomotor rhinitis includes symptoms like persistent nasal congestion, profuse watery or mucoid secretions, post-nasal drip, and sometimes sneezing (though typically less paroxysmal and less associated with itching than in allergic rhinitis). Headaches or a sensation of facial pressure may also occur. In some instances, the inflammatory or reactive process in vasomotor rhinitis can extend to involve one or more paranasal sinuses, leading to a non-allergic, vasomotor-driven sinusitis component.

Management Approaches for Vasomotor Rhinitis

The management of vasomotor rhinitis is primarily directed at identifying and avoiding known triggers, along with providing symptomatic relief, as there is no definitive "cure" for the underlying nasal hyperreactivity. Effective strategies include:

- Trigger Avoidance: This is the most critical step. Patients are encouraged to meticulously identify and then minimize or eliminate exposure to their specific environmental irritants or situational triggers. Maintaining a detailed symptom diary, correlating symptoms with potential exposures (foods, environments, activities, medications), can be invaluable in pinpointing these factors.

- Nasal Saline Irrigation: Regular use of isotonic or mildly hypertonic saline rinses or sprays helps to moisturize the nasal passages, clear accumulated mucus and irritants, and can improve overall nasal comfort and function.

- Intranasal Corticosteroids (INCS): Prescription INCS (e.g., fluticasone, mometasone, budesonide) can be quite effective in reducing nasal inflammation, congestion, and rhinorrhea in many patients with vasomotor rhinitis, similar to their utility in allergic rhinitis. Consistent daily use is typically required.

- Intranasal Antihistamines: Nasal sprays containing antihistamines like azelastine or olopatadine can provide significant relief from runny nose, congestion, and sneezing, even in non-allergic rhinitis. Their efficacy in this context may be due to their anti-inflammatory properties and potential mast cell stabilizing effects, beyond just H1-receptor antagonism.

- Intranasal Anticholinergics: Ipratropium bromide nasal spray is particularly effective for controlling profuse watery rhinorrhea (runny nose) by directly blocking parasympathetic nerve-mediated glandular secretions in the nose. It has less effect on congestion or sneezing.

- Oral Decongestants: Medications like pseudoephedrine may offer temporary relief from nasal congestion but should be used cautiously due to potential side effects (e.g., increased blood pressure, insomnia, nervousness) and are generally not recommended for long-term management.

- Capsaicin Nasal Spray: In some select cases of refractory vasomotor rhinitis, capsaicin (the active component of chili peppers) administered as a nasal spray has been used. It is thought to work by desensitizing nasal sensory nerves over time, but its initial application can be quite irritating and its use is not widespread.

- Surgical Options: For individuals with severe, persistent symptoms that are refractory to comprehensive medical management, surgical procedures might be considered. These can include turbinate reduction (to alleviate chronic nasal obstruction from hypertrophied turbinates) or, in very rare and specific circumstances, procedures like vidian neurectomy (aimed at interrupting the parasympathetic nerve supply to the nasal mucosa to reduce secretions and congestion).

Historically, interventions aimed at modulating underlying autonomic nervous system dysfunction or reducing nasal hyper-reactivity, such as intranasal novocaine or lidocaine injections, cryosurgery applied to the nasal cavity, electrophoresis with calcium chloride, or reflexology, have been explored. The goal of these approaches was often to improve nasal breathing and modulate local nerve responses, but their efficacy and role in contemporary practice require further substantiation through rigorous clinical research.

Differential Diagnosis: Allergic Rhinitis vs. Vasomotor Rhinitis

Accurately distinguishing between allergic rhinitis and vasomotor rhinitis is crucial for tailoring the most appropriate and effective management plan. While their symptoms can significantly overlap, several key features and diagnostic findings help differentiate these two common conditions:

| Feature | Allergic Rhinitis | Vasomotor Rhinitis (Non-Allergic Rhinitis) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Underlying Cause | An IgE-mediated hypersensitivity immune response to specific environmental or food allergens (e.g., pollens, dust mites, animal dander, molds, certain foods). | Nasal hyperreactivity or an exaggerated response of the nasal mucosa to various non-allergic, non-infectious triggers (e.g., irritants, weather changes, hormonal shifts, stress, certain medications). |

| Itching (Nose, Eyes, Palate, Ears) | Common, often prominent, and a hallmark symptom. | Usually absent or minimal. If present, typically mild. |

| Sneezing | Frequent, often occurring in characteristic paroxysms (bouts of multiple sneezes). | May occur, but generally less frequent and less paroxysmal than in allergic rhinitis. |

| Ocular Symptoms (Redness, Watering, Itching, Swelling) | Commonly present as allergic conjunctivitis, often co-occurring with nasal symptoms. | Rare, unless as a reflex lacrimation due to severe nasal irritation. True allergic conjunctivitis is absent. |

| Nasal Discharge Characteristics | Typically clear, thin, and watery (serous rhinorrhea). | Can be clear and watery, similar to allergic rhinitis, or sometimes thicker and more mucoid. May be profuse, especially with certain triggers (e.g., gustatory rhinitis). |

| Identifiable Triggers | Exposure to specific, identifiable allergens (seasonal or perennial). | Exposure to non-specific environmental irritants, changes in temperature/humidity, strong odors, smoke, stress, spicy foods, alcohol, hormonal fluctuations, certain systemic medications. |

| Seasonality of Symptoms | Often exhibits clear seasonality (e.g., symptoms worse during pollen seasons) or can be perennial if exposed to year-round allergens (e.g., dust mites, indoor molds, pets). | Usually perennial, though symptoms can fluctuate in intensity based on exposure to non-specific triggers. Less likely to show a distinct seasonal pattern tied to aeroallergens. |

| Associated Allergic Conditions | Frequently associated with other atopic diseases such as asthma, atopic dermatitis (eczema), and food allergies (part of the "allergic march"). | Less commonly associated with other classic allergic conditions. May sometimes be linked with conditions like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or certain hormonal imbalances. |

| Diagnostic Test Results | Positive skin prick tests (SPTs) or specific IgE (sIgE) blood tests confirm sensitization to relevant allergens that correlate with clinical symptoms. Nasal cytology may show eosinophilia. | Primarily a diagnosis of exclusion. Allergy tests (SPTs, sIgE) are typically negative for relevant allergens. A detailed clinical history focusing on triggers is paramount. Nasal cytology often shows neutrophils or is non-specific. |

When to Consult an ENT Specialist

While mild or occasional nasal symptoms can often be self-managed, it is advisable to consult an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist (otolaryngologist) if you or your child experience any of the following:

- Persistent or Chronic Symptoms: Nasal symptoms (such as congestion, runny nose, sneezing, facial pressure, or itching) that do not improve with standard over-the-counter medications or persist for more than a few weeks despite initial treatment.

- Significant Impact on Quality of Life: Symptoms that noticeably interfere with daily activities, sleep quality (e.g., causing snoring or sleep disturbance), school performance, or work productivity.

- Recurrent or Chronic Sinus Infections: Frequent episodes of acute sinusitis or symptoms suggestive of chronic rhinosinusitis that require repeated courses of antibiotics or do not fully resolve.

- Severe or Worrisome Symptoms: Symptoms such as severe or persistent facial pain or pressure, recurrent nosebleeds, loss of sense of smell (anosmia), or noticeable changes in hearing.

- Failure of Previous Treatments: If treatments prescribed by a primary care physician or general practitioner have not provided adequate relief or have caused intolerable side effects.

- Suspicion of Structural Nasal Problems: If there is a suspicion of underlying anatomical issues within the nose or sinuses, such as a significantly deviated nasal septum, persistent unilateral symptoms, or the presence of nasal polyps.

- Consideration for Advanced Diagnostics or Therapies: If there is a need for more specialized diagnostic procedures (e.g., nasal endoscopy, CT scan of the sinuses, comprehensive allergy testing) or consideration of advanced treatment options like allergen-specific immunotherapy or surgical intervention.

An ENT specialist is equipped to perform a thorough clinical evaluation, including a detailed examination of the nasal and pharyngeal passages (often with nasal endoscopy for direct visualization), to accurately diagnose the specific type of rhinitis or sinusitis. They can then develop a comprehensive and individualized treatment plan tailored to the patient's condition, which may involve advanced medical therapies, referral for allergy management, or surgical options if indicated.

References

- Bousquet J, Khaltaev N, Cruz AA, et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA(2)LEN and AllerGen). Allergy. 2008;63 Suppl 86:8-160.

- Wallace DV, Dykewicz MS, Oppenheimer J, Portnoy JM, Lang DM. Pharmacologic Treatment of Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis: Synopsis of Guidance From the 2017 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(12):876-881.

- Scadding GK, Kariyawasam HH, Scadding G, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis (Revised Edition 2017; First edition 2007). Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(7):856-889.

- Wise SK, Lin SY, Toskala E, et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Allergic Rhinitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8(2):108-352.

- Settipane RA. Other causes of rhinitis: mixed rhinitis, nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome (NARES), and vasomotor rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2001;22(1):11-14.

- Pattanaik D, Lieberman P. Vasomotor rhinitis: an update. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010 Apr;10(2):84-91.

- Small P, Keith PK, Kim H. Allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2018;14(Suppl 2):51.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis