Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Understanding Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis (Rhinosinusitis)

- Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis

- Diagnosis of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis

- Treatment Strategies for Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis

- Potential Complications of Maxillary Sinusitis and its Treatment

- Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Facial Pain/Pressure and Nasal Discharge

- When to Consult an ENT Specialist

- References

Understanding Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis (Rhinosinusitis)

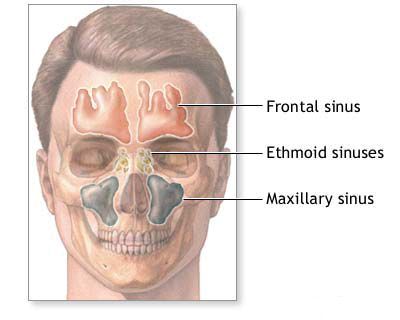

Chronic maxillary sinusitis, a form of chronic rhinosinusitis, is a persistent inflammation of the mucosal lining of the maxillary sinuses (the largest paranasal sinuses, located within the cheekbones) lasting for 12 weeks or longer. This condition is frequently associated with inflammation of the ethmoid sinuses (ethmoiditis), and the symptoms often arise from this combined sino-nasal pathology. Morphological changes characteristic of chronic maxillary sinusitis include swelling (edema), inflammatory cell infiltration of the nasal and sinus mucosa, and parietal thickening (thickening of the mucosal lining along the sinus walls).

Etiology and Predisposing Factors

The development of chronic maxillary sinusitis is typically multifactorial. Significant contributing factors include:

- Recurrent Acute Infections: Unresolved or frequent acute sinus infections can transition into a chronic inflammatory state.

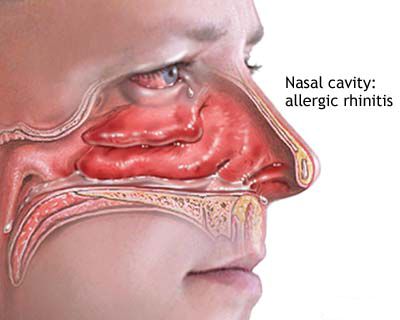

- Allergies: Allergic rhinitis causes chronic mucosal inflammation and swelling, which can obstruct sinus ostia (drainage openings).

- Anatomical Abnormalities in the Nasal Cavity: Conditions that impair natural ventilation and drainage of the sinuses, such as:

- Adenoid hypertrophy (enlarged adenoids), particularly in children.

- Deviated nasal septum.

- Nasal polyps.

- Concha bullosa (aerated middle turbinate) or hypertrophied turbinates.

- Variations in the ostiomeatal complex (the common drainage pathway for the maxillary, anterior ethmoid, and frontal sinuses).

- Impaired Immune Function: Immunodeficiency states or generally lowered body resistance can predispose to chronic infections.

- Odontogenic (Dental) Infections: Infections originating from the roots of the upper teeth (premolars and molars), whose apices are in close proximity to the maxillary sinus floor, can spread into the sinus.

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to irritants like cigarette smoke or air pollution, and possibly repeated chilling (cooling factor).

- Systemic Conditions: Hereditary factors, disturbances of the endocrine system, and co-morbidities can play a role. The size of the sinuses might also be a factor, with larger sinuses potentially being more susceptible.

- Biofilms: Bacterial biofilms, which are structured communities of bacteria resistant to antibiotics and host defenses, are thought to contribute significantly to the persistence of chronic rhinosinusitis.

Pathways of Infection

Infection of the paranasal sinuses, including the maxillary sinus, can occur through several routes:

- Rhinogenic (from the nasal cavity): This is the most common pathway. Infection spreads from the nasal cavity through the natural sinus ostia, often during episodes of rhinitis.

- Hematogenous (through the bloodstream): Less common, but infection can reach the sinuses via the bloodstream from a distant site of infection (e.g., during systemic infections like influenza).

- Odontogenic (from dental sources): As mentioned, infection from upper teeth roots.

- Direct Spread (by contact): Infection can spread from adjacent infected structures, such as purulent discharge leaking from other inflamed paranasal sinuses (e.g., ethmoid or frontal sinuses).

- Traumatic: Direct trauma to the face can introduce infection or create pathways for it.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis (Rhinosinusitis)

The symptoms of chronic maxillary sinusitis can be persistent but are often less intense than acute episodes, or they may involve periods of acute exacerbation. Common manifestations include:

- Nasal Congestion or Obstruction: Persistent difficulty breathing through the nose, often on one or both sides.

- Nasal Discharge: This can be:

- Anterior Rhinorrhea: Runny nose with mucus or purulent (thick, yellowish, or greenish) discharge.

- Posterior Nasal Drip: Sensation of mucus dripping down the back of the throat, often leading to throat clearing, chronic cough, or a sore throat.

- Facial Pain, Pressure, or Fullness: A dull ache, pressure, or feeling of heaviness over the affected maxillary sinus (cheek area), which may worsen when bending forward. Pain can sometimes radiate along the branches of the trigeminal nerve, affecting nearly the entire half of the face and potentially the upper teeth on the affected side.

- Reduced Sense of Smell (Hyposmia) or Loss of Smell (Anosmia).

- Headache: Often localized to the facial or frontal region.

- Bad Breath (Halitosis).

- Fatigue and General Malaise.

- Dental Pain: Pain in the upper teeth, particularly if the sinusitis is of odontogenic origin or if inflammation is severe near the tooth roots.

On physical examination (rhinoscopy), signs of chronic inflammation such as redness and swelling of the nasal mucous membranes are characteristic. Secretions may be visible in the middle nasal meatus (the drainage area for the maxillary sinus). Chronic catarrhal inflammation in children is often marked by mild symptoms, a slight general reaction, and catarrhal signs in the nasal cavity and sinuses. In chronic purulent inflammation, pus at the sinus ostia might only be detectable with micro-rhinoscopy or nasal endoscopy if not visible during standard rhinoscopy.

Forms of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis

Chronic maxillary sinusitis can manifest in various forms based on the nature of the inflammation and secretions:

- Chronic Catarrhal Sinusitis: Characterized by persistent mucosal inflammation with predominantly mucoid secretions.

- Chronic Purulent Sinusitis: Involves persistent bacterial infection with continuous or recurrent purulent discharge.

- Chronic Serous Sinusitis: May involve the accumulation of serous (thin, watery) fluid. This can be further divided:

- Idiopathic Form: Characterized by transudation of fluid that flows out of the sinus through its natural opening once accumulated.

- Retention Form: Occurs due to blockage of the sinus ostium, leading to the accumulation of pale yellow fluid. The fluid in serous inflammation is typically light yellow (similar to cyst fluid, which might be amber-colored) and lacks cholesterol crystals on the surface of washings.

- Chronic Hyperplastic/Polypoid Sinusitis: Characterized by significant mucosal thickening and often the formation of nasal polyps.

- Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS): A specific form driven by an allergic reaction to fungal elements, often leading to thick, tenacious "allergic mucin" and polyps.

- Odontogenic Sinusitis: Arising from dental infections.

Diagnosis of Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis

The diagnosis of chronic maxillary sinusitis is established through a comprehensive approach integrating clinical symptoms, findings from otorhinolaryngological examination, and often imaging studies. If an allergic component is suspected, allergological assessment is also necessary.

- Clinical History: A detailed history focusing on the duration (symptoms for 12 weeks or longer), nature, and severity of symptoms (nasal obstruction, discharge, facial pain/pressure, olfactory dysfunction), previous episodes of acute sinusitis, response to prior treatments, history of allergies, dental problems, and any relevant systemic conditions.

- Physical Examination (Otorhinolaryngological Examination):

- Anterior Rhinoscopy: Initial examination of the nasal cavities using a nasal speculum may reveal mucosal swelling, redness, the character of nasal discharge (mucoid, purulent), and sometimes visible polyps.

- Nasal Endoscopy: This is a crucial diagnostic tool. A rigid or flexible endoscope is passed into the nasal cavity to provide a magnified, detailed view of the middle meatus (where the maxillary sinus drains), the sinus ostium itself, the presence and nature of secretions or polyps, and the condition of the nasal mucosa.

- Imaging Studies:

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the Paranasal Sinuses: CT is the preferred imaging modality for evaluating chronic rhinosinusitis. It provides excellent anatomical detail, showing mucosal thickening, opacification (fluid or pus), air-fluid levels, bony changes (e.g., thickening or erosion), the patency of the ostiomeatal complex, and any associated anatomical variations or pathologies like polyps or odontogenic sources. CT scans are typically done without contrast unless a tumor or complicated infection is suspected.

- Plain X-rays (e.g., Waters view): Have limited sensitivity and specificity for chronic sinusitis compared to CT and are less commonly used today for detailed assessment, though they may show gross opacification or air-fluid levels.

- Maxillary Sinus Puncture (Antral Lavage/Washout): Historically, puncture of the maxillary sinus through the inferior nasal meatus using a trocar or needle was performed for both diagnostic (to obtain sinus contents for culture and cytology) and therapeutic (to wash out infected material and instill medication) purposes. Pre-puncture assessment included a complete blood count (including platelet count), coagulation studies (clotting and bleeding time). Anesthesia was typically achieved by topical application of 2% novocaine (procaine) or similar anesthetic to the nasal mucosa. The technique and feasibility depend on the child's age, as sinus volume and medial wall thickness vary. While still occasionally used, especially if endoscopy is unavailable or for specific indications, it has become less frequent with the advent of advanced endoscopic techniques. Potential complications of puncture include collapse, facial subcutaneous emphysema, bleeding, cheek abscess, septic conditions, and rarely, central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) leading to blindness.

- Allergy Testing: If an allergic component is suspected, skin prick tests or specific IgE blood tests (RAST) are indicated.

- Dental Evaluation: If an odontogenic source is suspected (e.g., unilateral maxillary sinusitis, foul-smelling discharge, dental pain), a thorough dental examination and appropriate dental imaging (e.g., panoramic X-ray, periapical X-rays, or cone-beam CT) are necessary.

Treatment Strategies for Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis (Rhinosinusitis)

The management of chronic maxillary sinusitis should be comprehensive, initiated early, and sustained if necessary. It often involves a combination of medical therapies and, in refractory cases, surgical intervention. The approach should be tailored to the individual patient, considering the specific form and severity of the disease.

General Principles and Conservative Management

The primary local treatment goal is to ensure free outflow of contents from the maxillary sinus and reduce mucosal inflammation. This involves:

- Medical Therapy:

- Nasal Saline Irrigation: Regular use of isotonic or hypertonic saline solutions to cleanse the nasal passages of mucus, irritants, and allergens, and to improve mucociliary function.

- Intranasal Corticosteroids: These are a cornerstone of medical management, reducing mucosal inflammation and swelling. Consistent long-term use is often required.

- Antibiotics: Longer courses of antibiotics (e.g., 3-6 weeks) may be prescribed, particularly if there is evidence of bacterial infection (e.g., purulent discharge, acute exacerbation). The choice should ideally be guided by culture and sensitivity results if available.

- Oral Corticosteroids: Short courses may be used for severe inflammation or to shrink nasal polyps, but their long-term use is limited by side effects.

- Mucolytics: Medications like guaifenesin may help thin tenacious mucus, although their efficacy in chronic sinusitis is debated.

- Addressing Contributing Factors: If necessary, surgical measures to improve nasal airflow and sinus drainage may be considered, such as removal of polypoid changes in the anterior ends of the turbinates or correction of a significantly deviated nasal septum (septoplasty).

- Facilitating Sinus Evacuation: To improve drainage, especially after anemization (application of vasoconstrictors like 0.1% adrenaline solution to the middle nasal meatus to shrink mucosa), positioning the patient's head forward and downward can be helpful, particularly in young children who cannot effectively blow their nose.

- Mechanical Cleaning (with caution): Irrigation of the nasal cavity with alkaline or saline solutions using a spray or rubber bulb can help remove thick mucus, pus, and crusts. However, this method must be used carefully to avoid forcing fluid into the Eustachian tubes, which can cause otitis media (middle ear infection); consequently, its application is sometimes limited, especially in young children.

Management of Allergic and Fungal Components

- Allergic Background: If chronic maxillary sinusitis occurs on an allergic background, hyposensitization therapy (allergen immunotherapy) and antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine, promethazine hydrochloride, suprastin, chloropyramine hydrochloride) are important. Diphenhydramine, due to its sedative effect, is often best used at night. Vitamin supplementation, especially during winter and spring, may be considered. Topical nasal preparations containing 1% diphenhydramine with 1-2% silver proteinate solution, or 0.5% prednisolone solution, have been historically used. For nasal crusts and heavy mucus, lubricating the nasal entrance with an indifferent ointment can be beneficial.

- Fungal Infections: If a fungal infection of the sinuses is diagnosed (e.g., fungus ball, allergic fungal rhinosinusitis), treatment may involve surgical removal of fungal debris and, in some cases, systemic or topical antifungal medications. Washing the sinuses with solutions of nystatin or levorin sodium salt (e.g., 5mg/ml or 10,000 IU/ml), aqueous gentian violet (0.01-0.1%), or chinosol (0.01%) has been described, often in conjunction with oral antifungal drugs and sometimes antibiotics like nystatin or levorin combined with sulfonamides (e.g., aethazolum).

If there is combined pathology, such as a purulent process in the lungs or bronchitis, appropriate concurrent treatment for these conditions is essential.

Interventional Procedures: Maxillary Sinus Probing

Maxillary sinus probing aims to restore patency of the natural ostium and improve the outflow of its contents. It is typically performed with the child seated, with the physician positioned slightly lower. The probe is carefully introduced into the middle nasal meatus towards the posterosuperior part of the uncinate process (lunate fissure region), where the natural maxillary sinus opening is located. All movements of the probe must be gentle, without force, attempting to bypass any obstacles. If significant bleeding occurs, probing should be stopped due to impaired orientation. Irrigation of the sinus through the natural opening via the probe has also been proposed.

Difficulties in probing can arise if the middle turbinate is closely apposed to the lateral nasal wall. In cases of hypertrophy of the middle or inferior turbinates, partial resection may be necessary. A deviated nasal septum, particularly obstructing the middle meatus, can also hinder probing. If nasal polyps are present in the nose or around the natural sinus ostia, polypectomy may be required first. If maxillary sinus probing is unsuccessful or deemed insufficient, surgical intervention is usually indicated.

Surgical Interventions: Endonasal Maxillary Sinus Dissection (Antrostomy)

Surgical treatment for chronic maxillary sinusitis, when indicated by strict criteria and after careful selection of method, can significantly reduce disease duration and prevent serious consequences. The primary goal of surgery is to create a wide, resistant drainage pathway and ensure good outflow of contents from the maxillary sinus. This not only helps eliminate secretions that constantly irritate the nasal mucosa but also improves blood circulation, mucosal health (trophism), ventilation, and aeration, creating conditions conducive to the resolution of the inflammatory process.

In recent years, particularly in pediatric practice, the approach to maxillary sinus surgery has become more conservative, with a preference for sparing endonasal methods (Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery - FESS) over more radical extra-nasal (external) approaches. FESS offers several advantages, including better visualization, preservation of normal anatomy and physiology, and reduced morbidity. During FESS for maxillary sinusitis, the surgeon aims to enlarge the natural maxillary ostium or create a new opening (middle meatal antrostomy) into the sinus, removing only diseased mucosa and bone while preserving as much healthy tissue and normal nasal cavity architectonics as possible. Impact on developing dental structures is also a consideration in children.

Endonasal maxillary sinus surgery is performed under general or local anesthesia. For local anesthesia, the nasal mucosa in the area of intervention is anesthetized (e.g., with topical 3% cocaine solution, though modern practice often uses lidocaine with epinephrine). In some cases, topical administration of 0.25-0.5% novocaine (procaine) solution may be used. The dissection can be approached through the middle or inferior nasal meatus, with the middle meatal approach being physiologically preferred. If hypertrophied turbinates obstruct access, they may be partially resected or gently medialized/outfractured. The maxillary sinus is then opened using specialized instruments (e.g., sharp spoons, antrum punches, microdebriders) typically at the site of its natural ostium or by creating an accessory opening. The opening is enlarged sufficiently to allow for adequate drainage and ventilation. Any pathological contents (pus, thick mucus, polyps, fungal debris) are removed from the sinus. To minimize postoperative reactive tissue edema, the sinus is often not packed, or a dissolvable spacer/dressing might be used. If a cotton swab is used, it's typically placed only in the newly created anastomosis for about 1 day and then removed, followed by regular sinus irrigations.

Endoscopic guidance is crucial for performing these operations with precision, allowing for thorough examination of the sinus cavity, its ostium, and the ostium of the nasolacrimal duct. If damage is extensive or it's suspected that pathological content is not completely removed, or if there are necrotic bone changes, a combined approach or a more extensive procedure might be necessary.

Alternative Surgical Approaches and Shunt Placement

Traditional radical maxillary sinus surgery (e.g., Caldwell-Luc procedure) involved an external approach through the canine fossa (under the upper lip). This approach allows wide access to the sinus but carries risks such as damage to dental nerves (causing tooth numbness), injury to the infraorbital nerve (causing cheek numbness), significant facial swelling, and potential for long-term complications. Therefore, it is used more sparingly today, typically for specific indications like tumors, extensive fungal disease, or complex trauma, especially in children due to concerns about facial growth and tooth development.

Instead of repeated punctures, placement of indwelling drainage tubes or shunts (often made of alloplastic materials like silicone or PTFE) into the maxillary sinus can be used for prolonged access for irrigation and medication instillation. These shunts can be inserted in children of any age and adults, sometimes under endoscopic guidance, via a needle puncture, typically beneath the inferior turbinate aiming towards the sinus floor for better fixation. This method is considered more gentle than repeated punctures or open surgery. Shunts may remain in place for up to 10 days or until recovery. Insertion can be facilitated using a fluted probe or under direct surgical optic control.

In some cases, particularly with periostitis, an operation via a pear-shaped ridge approach may be performed. An incision is made anteriorly in the nasal cavity, and soft tissues are elevated to expose the lower edge of the piriform aperture, through which the sinus is opened. The opening created is similar to that of an extranasal approach but with potentially less external morbidity.

Potential Complications of Maxillary Sinusitis and its Treatment

Untreated or inadequately managed chronic maxillary sinusitis can lead to complications, although severe ones are less common than with acute infections. Complications of the disease itself or its surgical treatment can include:

- Orbital Complications: Due to the proximity of the maxillary sinus to the orbit (eye socket), infection can spread, potentially causing preseptal cellulitis, orbital cellulitis, subperiosteal abscess, or rarely, optic neuritis.

- Intracranial Complications: Extremely rare, but possible with severe, aggressive infections, include meningitis, epidural abscess, or cavernous sinus thrombosis.

- Mucocele or Pyocele Formation: Chronic obstruction of the sinus ostium can lead to the formation of a mucocele (a mucus-filled, expansile cyst) or pyocele (if the mucocele becomes infected). These can erode surrounding bone.

- Osteomyelitis: Inflammation and infection of the bone surrounding the maxillary sinus.

- Dental Complications: If sinusitis is odontogenic, it can affect adjacent teeth. Conversely, sinus surgery can rarely affect sensation in upper teeth.

- Complications of Sinus Puncture/Surgery:

- Bleeding (epistaxis).

- Infection at the surgical site.

- Facial swelling or bruising.

- Subcutaneous emphysema (air trapped under the skin).

- Cheek abscess (especially with Caldwell-Luc).

- Numbness of the cheek, upper lip, or teeth (due to infraorbital or dental nerve injury).

- Nasolacrimal duct injury leading to excessive tearing (epiphora).

- Synechiae (scar tissue adhesions) within the nasal cavity.

- Failure of the antrostomy to remain patent, leading to recurrent sinusitis.

- Rarely, more serious complications like CSF leak or orbital injury during FESS.

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Facial Pain/Pressure and Nasal Discharge

Chronic symptoms in the maxillary sinus region require careful differentiation from other conditions:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis | Persistent symptoms >12 weeks; facial pain/pressure over cheeks, purulent or mucoid nasal discharge (anterior/posterior), nasal obstruction, hyposmia. CT shows maxillary sinus mucosal thickening/opacification. |

| Allergic or Non-Allergic Rhinitis | Nasal congestion, rhinorrhea (often watery in allergy), sneezing, itching (in allergy). Sinus imaging may be normal or show incidental mucosal thickening without frank sinusitis. |

| Odontogenic Pain/Infection | Pain often localized to a specific tooth or teeth in the upper jaw, may be exacerbated by chewing or temperature changes. Dental examination and imaging are key. May cause secondary maxillary sinusitis. |

| Trigeminal Neuralgia | Paroxysmal, severe, electric shock-like pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve (V2 branch for maxillary region). Often triggered by light touch or specific movements. Typically no nasal discharge. |

| Migraine or Other Headaches | Headache pattern characteristic of migraine (throbbing, unilateral, nausea, photophobia) or tension-type. "Sinus headache" is often a misdiagnosed migraine. |

| Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction | Pain in jaw joint, ear, or side of face, often with clicking, popping, or limited jaw movement. Can refer pain to cheek area. |

| Nasal Polyposis (CRSwNP) | Severe nasal obstruction, significant loss of smell. Polyps visible on endoscopy/CT. Maxillary sinuses are frequently involved. |

| Maxillary Sinus Tumor (Benign or Malignant) | Unilateral symptoms, persistent pain, facial swelling, numbness, bloody discharge, loose teeth, or visual changes can be red flags. Requires imaging and biopsy. |

When to Consult an ENT Specialist

Patients experiencing symptoms suggestive of chronic maxillary sinusitis should consult an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist if:

- Symptoms (nasal blockage, facial pain/pressure, discharge, altered smell) persist for more than 12 weeks.

- Recurrent episodes of acute sinusitis occur frequently (e.g., 3-4 or more per year).

- Symptoms significantly impact daily activities, sleep, or overall quality of life.

- Over-the-counter medications and initial treatments from a primary care physician are ineffective.

- There are signs of potential complications, such as swelling around the eye, severe headache, vision changes, or persistent fever.

- Unilateral symptoms, bloody nasal discharge, or facial numbness are present, which could indicate a more serious underlying condition.

An ENT specialist can perform a thorough evaluation, including nasal endoscopy and CT scanning if indicated, to establish an accurate diagnosis and develop a tailored, comprehensive treatment plan.

References

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020 (EPOS 2020). Rhinology. 2020 Feb 20;58(Suppl S29):1-464.

- Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015 Apr;152(2 Suppl):S1-S39.

- Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, et al. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003 Sep;129(3 Suppl):S1-S32.

- Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Quantification for staging sinusitis. The Staging and Therapy Group. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1995 May;167:17-21.

- Stammberger H, Posawetz W. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Concept, indications and results of the Messerklinger technique. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;247(2):63-76.

- Kennedy DW. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Technique. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985 Nov;111(11):643-9.

- Albu S, Gocea A, Mitre I. Endoscopic middle meatal antrostomy: long-term results in chronic maxillary sinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011 May-Jun;25(3):196-200.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis