Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

Understanding Chlamydial Rhinitis

Chlamydial rhinitis is an inflammation of the nasal mucous membranes caused by infection with Chlamydia species, most commonly *Chlamydia trachomatis*. Chlamydiae are unique obligate intracellular bacteria, meaning they occupy an intermediate position between viruses and typical bacteria. Like viruses, they require host cells to multiply, but like bacteria, they possess metabolic machinery and are susceptible to certain antibiotics, including tetracyclines, macrolides, and some sulfa drugs.

Nature of Chlamydia and Systemic Involvement

*Chlamydia trachomatis* is well-known as a cause of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) affecting the urogenital tract, as well as ocular infections (trachoma and inclusion conjunctivitis). It can also affect the mucous membranes of the respiratory tract (including the nose, pharynx, and lungs), and less commonly, the lower gastrointestinal tract. In some cases, chlamydial infection can lead to reactive arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis, a triad historically known as Reiter's syndrome (now more commonly referred to as reactive arthritis).

Given that chlamydial infections often primarily affect the genital tract, individuals presenting with chlamydial rhinitis (especially adults) may also have a concurrent infection in the urogenital organs (e.g., nonspecific urethritis in males, cervicitis in females). Therefore, a diagnosis of chlamydial rhinitis may prompt referral to a urologist or gynecologist for comprehensive STI screening and management. In approximately 20% of cases, chlamydial infections, including those manifesting as rhinitis, can be accompanied by middle ear inflammation (otitis media) also caused by Chlamydia.

Chlamydial Rhinitis in Newborns and Infants

Chlamydial rhinitis is particularly significant in newborns and young infants, occurring in up to 20% of infants born to mothers with untreated chlamydial cervical infection. Infection is typically acquired during passage through an infected birth canal. Due to the narrowness of their nasal passages, even slight mucosal edema from chlamydial inflammation can lead to significant nasal obstruction. This can result in:

- Impaired Nasal Breathing: Leading to mouth breathing.

- Feeding Difficulties: Infants are obligate nasal breathers, and nasal obstruction makes sucking and swallowing difficult, forcing them to interrupt feeding to breathe through the mouth.

- Sleep Disturbances: Including dyspnea (difficulty breathing), choking episodes, and even apnea (temporary cessation of breathing) during sleep.

Chlamydial infection causing acute rhinitis in infants can be particularly severe because their immune mechanisms against this pathogen are not yet fully developed. The downward spread of chlamydial infection from the nasopharynx can lead to more serious lower respiratory tract complications such as rhinopharyngitis, laryngotracheitis, bronchitis, and chlamydial pneumonia (afebrile pneumonia of infancy), which characteristically presents with a staccato cough and can cause significant respiratory distress. In such cases, mucus in the child's respiratory tract may produce audible "croaking" sounds.

Diagnosis of Chlamydial Rhinitis

Diagnosis of chlamydial rhinitis involves:

- Clinical Suspicion: Based on persistent rhinitis, especially in newborns with a maternal history of chlamydial infection or in adults with risk factors for STIs.

- Specimen Collection: Swabs from the nasopharynx or nasal discharge.

- Laboratory Testing:

- Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests (NAATs): These are the most sensitive and specific tests for detecting *Chlamydia trachomatis* DNA or RNA.

- Cell Culture: Historically the gold standard, but less sensitive than NAATs and more technically demanding.

- Direct Fluorescent Antibody (DFA) tests: Less sensitive than NAATs and culture.

- Evaluation for Other Sites: In adults, testing for urogenital chlamydial infection is crucial. In newborns, evaluation for chlamydial conjunctivitis and pneumonia should be performed.

Treatment of Chlamydial Rhinitis

General Principles and Prevention

Treatment of chlamydial rhinitis focuses on eradicating the infection with appropriate antibiotics. Systemic therapy is required due to the intracellular nature of Chlamydia. Treatment in adults may sometimes be managed on an outpatient basis, but severe or complicated cases, or treatment in vulnerable populations like infants, may necessitate hospitalization to ensure adequate and intensive therapy. A full course of antibiotics, typically lasting from 1 to several weeks depending on the chosen regimen and severity, is essential. With appropriate treatment, chlamydial rhinitis can usually be cured without long-term complications, and relapses are uncommon if the full course is completed and any concurrent urogenital infection is also treated (along with partners, in adults).

Despite the potential for cure, a frivolous attitude towards chlamydial rhinitis should be avoided due to its potential for complications, especially in infants, and its association with STIs in adults. Preventing the neglect or chronic progression of the infection is important.

Chlamydial conjunctivitis (and potentially associated rhinitis) has historically been linked to outbreaks among visitors of public swimming facilities, leading to terms like "swimming pool conjunctivitis" or "bath/basin rhinitis." This highlights the potential for transmission in inadequately chlorinated water, although this is a less common route than sexual or perinatal transmission. Therefore, individuals diagnosed with active chlamydial infection (e.g., conjunctivitis) should refrain from using public swimming pools until treated. Strict adherence to water chlorination standards in swimming pools is crucial for preventing the spread of such infections.

Treatment in Newborns and Infants

Treatment of acute chlamydial rhinitis (and associated pneumonia or conjunctivitis) in young children and infants can be challenging. Topical agents applied to the nose are generally ineffective against the intracellular chlamydial infection.

- Systemic Antibiotics: Oral macrolide antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment.

- Erythromycin: Historically, erythromycin base or ethylsuccinate (e.g., 50 mg/kg/day in 4 divided doses for 14 days) was commonly used. However, it has gastrointestinal side effects and a risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (IHPS), especially if given in the first few weeks of life.

- Azithromycin: A shorter course of oral azithromycin (e.g., 20 mg/kg/day for 3 days, or a single dose regimen) is now often preferred due to better tolerance and simpler dosing, though the risk of IHPS, while lower, should still be considered.

- Supportive Care:

- If bacterial superinfection is suspected to be complicating the chlamydial rhinitis, specific antiparasitic (antibacterial) nasal instillation solutions might be considered, though systemic antibiotics for Chlamydia are primary.

- Vasoconstrictor nasal drops (e.g., oxymetazoline 0.025% for infants) may be used very sparingly and for a short duration (e.g., only before feeding) to relieve severe nasal obstruction that interferes with feeding. Their effect is short-lived.

- Gentle aspiration of mucus from the nasal cavity with a bulb syringe before feeding can help improve breathing and feeding.

It is essential to treat the mother and her sexual partner(s) if an infant is diagnosed with chlamydial infection to prevent reinfection and manage the maternal STI.

Understanding Trichomonas Rhinitis

Etiology and Clinical Presentation in Newborns

Trichomonas rhinitis is a rare condition caused by infection of the nasal mucosa with *Trichomonas vaginalis*, a flagellated protozoan parasite primarily known for causing trichomoniasis, a common STI. In newborns, Trichomonas rhinitis is acquired perinatally during passage through an infected maternal birth canal. *Trichomonas vaginalis* can be found in the genital tract of more than 25% of pregnant women, many of whom may be asymptomatic.

Neonatal infection with *Trichomonas vaginalis* typically manifests within the first few weeks of life. While respiratory tract involvement is less common than urogenital infection in adults, it can occur. Clinical presentation in newborns often includes:

- Conjunctivitis: Often the first sign, similar to other forms of neonatal conjunctivitis.

- Rhinitis: Typically develops after conjunctivitis, around 3 weeks of age. Symptoms include nasal discharge, which can be watery, mucoid, or sometimes bloody, and nasal obstruction.

- Unilateral Epistaxis (Nosebleed): Bleeding from one side of the nose can be a characteristic feature.

- Nasal Mucosal Changes: Examination of the nasal cavity may reveal diffuse inflammation and sometimes granulation-like changes of the mucous membrane.

- Pneumonia: In some cases, *Trichomonas vaginalis* can also cause pneumonia in newborns, presenting with respiratory distress.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Trichomonas Rhinitis

Diagnosis involves:

- Microscopic Examination: Wet mount preparation of nasal discharge (or discharge from the eyes, or maternal vaginal secretions) can reveal motile trichomonads.

- Culture: Specialized culture media (e.g., Diamond's medium) can be used to grow *Trichomonas vaginalis*.

- NAATs: Nucleic acid amplification tests are also available for detecting *Trichomonas vaginalis* and are highly sensitive.

Treatment of Trichomonas rhinitis (and other neonatal trichomoniasis manifestations) in the infant involves systemic antiparasitic medication:

- Metronidazole: This is the drug of choice. The recommended dose for neonates is typically 10-30 mg/kg/day orally, divided into doses, for 5-7 days. The exact dosing regimen should be determined by a pediatrician experienced in neonatal infections.

Historical treatments mentioned, such as ampicillin followed by erythromycin, are not effective against *Trichomonas vaginalis*. Ampicillin and erythromycin are antibiotics used for bacterial infections; Trichomonas is a protozoan. Correct identification of the pathogen is crucial for appropriate therapy.

It is also imperative to treat the infected mother and her sexual partner(s) for trichomoniasis to prevent reinfection and further transmission.

Differential Diagnosis of Persistent Rhinitis in Infants

Persistent or severe rhinitis in an infant requires careful evaluation to differentiate between various infectious and non-infectious causes:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Chlamydial Rhinitis | Onset typically 1-4 weeks (can be later); persistent nasal congestion/discharge; often associated with conjunctivitis and/or afebrile pneumonia with staccato cough; confirmed by NAAT for *C. trachomatis*. |

| Trichomonas Rhinitis | Onset around 3 weeks, often after conjunctivitis; nasal discharge, possible unilateral epistaxis; confirmed by microscopy/culture/NAAT for *T. vaginalis* from infant and mother. |

| Gonococcal Rhinitis | Early onset (first 2 weeks); profuse purulent, sometimes bloody discharge; marked mucosal inflammation; confirmed by Gram stain/culture/NAAT for *N. gonorrhoeae*. |

| Viral Upper Respiratory Infection (Common Cold) | Common; watery discharge initially, may become mucopurulent; associated with cough, sneezing, mild fever; usually self-limiting. |

| Bacterial Rhinosinusitis (Secondary) | May follow a viral URI; persistent purulent discharge, congestion; common respiratory pathogens. |

| Congenital Syphilis ("Snuffles") | Persistent, often bloody or mucopurulent nasal discharge ("snuffles") starting in early infancy; other signs of congenital syphilis (rash, bone changes). Positive syphilis serology. |

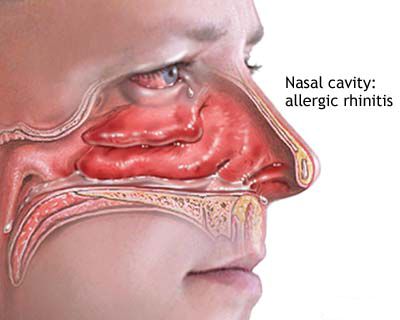

| Allergic Rhinitis | Less common in very early infancy but possible; clear watery discharge, sneezing, nasal itching; often family history of atopy. |

| Anatomical Abnormalities (e.g., Choanal Atresia/Stenosis) | Presents with severe nasal obstruction from birth (especially if bilateral); cyclic cyanosis with feeding in bilateral atresia. Diagnosed by inability to pass catheter or imaging. |

When to Consult a Specialist

Consultation with an ENT specialist, pediatrician, or infectious disease specialist is recommended if:

- An infant or newborn develops persistent, severe, or purulent nasal discharge, especially if accompanied by feeding difficulties, respiratory distress, or conjunctivitis.

- Chlamydial or Trichomonas infection is suspected or diagnosed in any individual with nasal symptoms.

- There is a maternal history of untreated Chlamydia or Trichomonas infection during pregnancy and the infant develops respiratory or nasal symptoms.

- Symptoms of rhinitis do not improve with standard care or recur frequently.

Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for appropriate treatment and prevention of complications, particularly in vulnerable neonatal populations.

References

- Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, et al. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021 Jul 23;70(4):1-187.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Chlamydia trachomatis Infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:271-279.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Trichomonas vaginalis Infections. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2021–2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021:802-804.

- Hammerschlag MR. Chlamydia trachomatis and Chlamydia pneumoniae infections in children and adolescents. Pediatr Rev. 2004 Feb;25(2):43-51.

- Schwebke JR, Burgess D. Trichomoniasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004 Oct;17(4):794-803.

- Black-Payne C. Neonatal Chlamydial Infections. Medscape. Updated: Nov 08, 2022. (Refer to latest version)

- Laga M, Manoka A, Kivuvu M, et al. Non-ulcerative sexually transmitted diseases as risk factors for HIV-1 transmission in women: results from a cohort study. AIDS. 1993 Jan;7(1):95-102. (Context for STIs)

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis