Idiopathic periodontal disease, periodontomas

- Understanding Idiopathic Periodontal Diseases

- Periodontomas (Tumors and Tumor-Like Formations of the Periodontium)

- Diagnostic Considerations and Investigations

- General Principles of Management

- Differential Considerations for Rapid or Unusual Periodontal Destruction

- Prognosis and Importance of Multidisciplinary Care

- When to Suspect and Refer

- References

Understanding Idiopathic Periodontal Diseases

Definition and General Clinical Signs

Idiopathic periodontal diseases encompass a group of conditions where the origin or exact cause of the periodontal destruction is not clearly understood or is not attributable to common factors like plaque-induced inflammation alone. These diseases often present with a rapidly progressive and generalized lesion affecting all periodontal tissues (gingiva, periodontal ligament, alveolar bone, and cementum). This can lead to significant and swift deterioration of dental support.

The general clinical signs characteristic of this group of idiopathic (of unknown or unclear origin) periodontal diseases include:

- Steady and Rapid Progression: Pronounced and often aggressive destruction of all periodontal tissues. This destructive process can lead to the loss of teeth within a relatively short period, sometimes as quickly as 2-3 years from onset if unmanaged.

- Rapidly Developing Tooth Displacement and Loosening (Mobility): Teeth become noticeably mobile and may drift or change position quickly.

- Peculiar or Atypical X-ray Picture: Radiographic findings may show unusual patterns or rates of bone loss that do not always correlate with the amount of local irritants (plaque/calculus) present.

These conditions are often distinguished from common chronic periodontitis by their aggressive nature, early onset (in some forms), or association with underlying systemic factors that may not be immediately obvious.

Role of the Dental Therapist and Specialist Referral

The role of a general dental therapist or general dentist in the examination and initial management of patients presenting with signs suggestive of idiopathic or rapidly progressive periodontal diseases is primarily:

- To establish a presumptive or provisional diagnosis based on clinical and radiographic findings.

- To recognize the atypical or aggressive nature of the disease.

- Crucially, to refer the patient promptly to a specialist of the appropriate profile for definitive diagnosis and management. This often involves a periodontist and may require consultation with a maxillofacial surgeon, physician, or other medical specialists (e.g., hematologist, immunologist, geneticist) depending on the suspected underlying etiology.

- In the future, after specialist intervention, the dental therapist may be involved in conducting symptomatic therapy and supportive periodontal maintenance as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Examples of Conditions with Idiopathic Periodontal Manifestations

While "idiopathic" means the exact cause is unknown, this category often includes conditions where systemic factors play a major role, leading to periodontal destruction that is disproportionate to local factors. Examples that historically or clinically might fall under this umbrella (though specific syndromes are now better defined) include:

- Aggressive Periodontitis (formerly Early-Onset Periodontitis): Characterized by rapid attachment loss and bone destruction, often affecting younger individuals, and may have a familial aggregation. Specific microbial profiles (e.g., *Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans*) and host immune response defects are implicated. (Note: Newer classifications integrate aggressive forms into the general periodontitis staging/grading system).

- Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease: Several systemic conditions can lead to severe and rapidly progressive periodontal lesions. These include:

- Hematological disorders (e.g., neutropenia, leukemia).

- Genetic disorders (e.g., Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome, Down syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Chediak-Higashi syndrome).

- Immunodeficiency disorders.

- Other rare conditions where severe periodontal breakdown is a primary feature without a readily identifiable common cause.

Periodontomas (Tumors and Tumor-Like Formations of the Periodontium)

Overview and Common Examples

The category of periodontal diseases also encompasses a range of tumors and tumor-like formations that arise from or affect the periodontal tissues. These can be benign or, rarely, malignant. They are distinct from inflammatory periodontal diseases like gingivitis and periodontitis, although they can sometimes coexist or present with similar initial symptoms (e.g., gingival swelling).

Common examples of periodontomas include:

- Epulis: This is a non-specific clinical term for any benign, localized tumor-like growth on the gingiva. Histopathologically, epulides can be further classified:

- Fibrous Epulis (Irritation Fibroma): A common, firm, pale pink, sessile or pedunculated growth, usually arising from chronic irritation.

- Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma (Giant Cell Epulis): A reddish-purple, often hemorrhagic lesion, typically found on the gingiva or edentulous alveolar ridge, containing multinucleated giant cells.

- Pyogenic Granuloma (Vascular Epulis, Pregnancy Tumor): A highly vascular, bright red, often ulcerated and easily bleeding lesion, which is a reactive inflammatory hyperplasia, not a true granuloma or pyogenic infection. Common during pregnancy due to hormonal changes.

- Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma: A firm, reactive gingival lesion containing bone or cementum-like calcifications.

- Gingival Fibromatosis: A rare condition characterized by slow, progressive, generalized or localized benign overgrowth of the gingival fibrous connective tissue. It can be hereditary (hereditary gingival fibromatosis) or drug-induced (e.g., by phenytoin, cyclosporine, nifedipine). The gums appear firm, dense, and pale pink, and can cover the teeth significantly.

- Other Benign Tumors: Less commonly, other benign mesenchymal or epithelial tumors can arise in the periodontium (e.g., lipoma, neurofibroma, papilloma).

- Malignant Tumors: Primary malignant tumors of the periodontium are rare but can include squamous cell carcinoma of the gingiva, sarcomas, or metastatic lesions. These present with more aggressive features like rapid growth, ulceration, pain, bone destruction, and tooth mobility.

Diagnosis and Management Approach for Periodontomas

The diagnosis and treatment of periodontomas are primarily carried out by dental surgeons, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, or periodontists, often in collaboration with oral pathologists.

The role of the general dental therapist or dentist in cases where a periodontoma is suspected is crucial for early detection and appropriate referral. This involves:

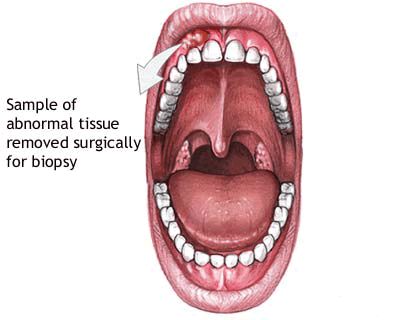

- Clinical Examination: Identifying any unusual growths, swellings, or changes in the gingival or periodontal tissues.

- Making a Preliminary (Provisional) Diagnosis: Based on the clinical appearance and history.

- Referral: Promptly referring the patient to an appropriate specialist or medical institution (e.g., department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, specialized periodontal clinic, or oncology center if malignancy is suspected) for comprehensive examination, definitive diagnosis (often requiring biopsy and histopathological analysis), and treatment.

Treatment for periodontomas varies widely depending on the specific diagnosis:

- Benign Reactive Lesions (e.g., fibrous epulis, pyogenic granuloma): Often treated by conservative surgical excision along with elimination of any local irritants (e.g., calculus, overhanging restorations).

- Gingival Fibromatosis: Management may involve surgical reduction of the overgrown tissue (gingivectomy/gingivoplasty), meticulous oral hygiene, and addressing any underlying cause (e.g., discontinuing an offending drug if possible).

- Malignant Tumors: Require multidisciplinary oncological management, typically involving surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy.

Diagnostic Considerations and Investigations for Idiopathic Periodontal Diseases and Periodontomas

Given the diverse nature of these conditions, a thorough diagnostic workup is essential:

- Comprehensive Medical and Dental History: Including family history, systemic conditions, medications, onset and progression of symptoms.

- Detailed Clinical Periodontal Examination: Probing depths, attachment levels, bleeding on probing, tooth mobility, furcation involvement, assessment of gingival lesions (size, shape, color, consistency).

- Radiographic Evaluation: Full-mouth periapical radiographs and bitewings, or panoramic radiographs, are essential to assess bone levels, patterns of bone loss, and detect any osseous changes associated with tumors or cysts. CT scans may be needed for complex cases or suspected tumors involving bone.

- Biopsy and Histopathological Examination: Mandatory for any suspicious lesion or tumor-like growth (periodontoma) to establish a definitive diagnosis and rule out malignancy. For rapidly progressive or atypical periodontitis, biopsy might occasionally be considered to rule out underlying systemic diseases manifesting in the periodontium.

- Microbiological Analysis: May be useful in cases of aggressive periodontitis to identify specific pathogenic bacteria and guide antibiotic therapy.

- Blood Tests and Systemic Evaluation: If an underlying systemic disease is suspected as contributing to idiopathic periodontal destruction (e.g., CBC with differential, glucose levels, tests for autoimmune markers, genetic testing for specific syndromes).

- Consultation with Medical Specialists: As needed (e.g., hematologist, endocrinologist, rheumatologist, geneticist, oncologist).

General Principles of Management

The management approach depends heavily on the specific diagnosis:

- Idiopathic Periodontal Diseases (often aggressive forms): Treatment typically involves intensive non-surgical periodontal therapy (scaling and root planing), often combined with systemic antibiotics. Surgical periodontal therapy (flap surgery, regenerative procedures) may be necessary. Long-term, rigorous periodontal maintenance is crucial. Management of any identified systemic contributing factors is paramount.

- Periodontomas:

- Benign Reactive Lesions: Surgical excision and removal of local irritants.

- Gingival Fibromatosis: Surgical reduction (gingivectomy) and meticulous oral hygiene. If drug-induced, consultation with the prescribing physician to consider alternative medications.

- Malignant Tumors: Requires oncological management (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy) by a specialized team.

Differential Considerations for Rapid or Unusual Periodontal Destruction

When faced with unusually rapid or severe periodontal destruction, especially if it seems disproportionate to local factors, clinicians must consider a broad differential:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Aggressive Periodontitis (Forms now part of Staging/Grading) (Relates to severe forms of Periodontitis, potentially aspects of Idiopathic periodontal disease or Severe Chronic Generalized Periodontitis) | Rapid bone/attachment loss, often in younger individuals (<35), familial aggregation possible, specific microbial profile (e.g., *A. actinomycetemcomitans*). Plaque levels may not be extremely high. |

| Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Disease (e.g., Papillon-Lefèvre, Neutropenia, Leukemia, uncontrolled Diabetes) (May lead to severe forms like Severe Chronic Generalized Periodontitis or features of Idiopathic periodontal disease) | Severe periodontal destruction often at an early age, associated with signs/symptoms of the underlying systemic condition. Requires medical diagnosis and management of the systemic disease. |

| Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis / Periodontitis (NUP) (NUP is an extension of NUG into deeper periodontal tissues, relating to Periodontitis) | Acute onset, severe pain, gingival necrosis/ulceration, rapid bone loss (in NUP). Often associated with severe immunosuppression (e.g., HIV/AIDS), stress, malnutrition. |

| Malignant Neoplasms (e.g., Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Leukemia, Lymphoma, Sarcoma invading periodontium) (Can present as Periodontomas or mimic severe Periodontitis) | Localized or diffuse rapidly destructive lesion, may present as swelling, ulceration, pain, loose teeth. Biopsy is essential. |

| Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (Histiocytosis X) (Can mimic severe Periodontitis or aspects of Idiopathic periodontal disease) | Rare disorder; can cause lytic bone lesions, "floating teeth" appearance on radiographs, gingival inflammation/ulceration. Biopsy confirms diagnosis. |

Prognosis and Importance of Multidisciplinary Care

The prognosis for idiopathic periodontal diseases with rapid progression is often guarded and depends on the specific underlying cause (if identified), the extent of destruction at diagnosis, and the patient's response to treatment and ability to maintain meticulous oral hygiene. Early diagnosis and aggressive, often multidisciplinary, management offer the best chance of stabilizing the condition and preserving teeth for as long as possible.

For periodontomas, the prognosis for benign lesions is generally excellent after complete excision. For malignant tumors, the prognosis depends on the tumor type, stage, and response to oncological treatment.

A collaborative approach involving dentists, periodontists, oral/maxillofacial surgeons, oral pathologists, and relevant medical specialists is often essential for managing these complex conditions.

When to Suspect and Refer

General dentists and dental therapists should maintain a high index of suspicion and consider prompt referral when encountering:

- Rapidly progressive periodontal destruction, especially in younger individuals or if disproportionate to local factors.

- Periodontal disease that is unresponsive to conventional therapy.

- Unusual gingival growths, swellings, or ulcerations.

- Periodontal manifestations associated with known or suspected systemic diseases.

- Any lesion where malignancy cannot be definitively ruled out clinically.

Early referral to appropriate specialists is key to timely diagnosis and effective management, which can significantly impact long-term outcomes.

References

- Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999 Dec;4(1):1-6. (Historical classification context)

- Papapanou PN, Sanz M, Buduneli N, et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018 Jun;89 Suppl 1:S173-S182. (Current classification which incorporates aggressive forms)

- Albandar JM. Aggressive periodontitis: case definition and diagnostic criteria. Periodontol 2000. 2014 Jun;65(1):13-26.

- Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Chi AC. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016. (Covers periodontomas and reactive lesions)

- Hart TC, Shapira L. Papillon-Lefèvre syndrome. Periodontol 2000. 1994 Jun;5:88-100.

- Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Odontogenic Tumors and Allied Lesions. Quintessence Publishing; 2004. (Context for tumor-like conditions)

- Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999 Dec;4(1):39-53. (Historical context for aggressive forms)

- Scully C, Felix DH. Oral medicine--update for the dental practitioner: orofacial Pain. Br Dent J. 2005 Oct 22;199(8):497-504. (Broader context for oral lesions)

See also

- Dental anatomy

- Dental caries

- Periodontal disease:

- Chronic catarrhal gingivitis

- Chronic generalized periodontitis of moderate severity

- Chronic hypertrophic gingivitis

- Chronic mild generalized periodontitis

- Idiopathic periodontal disease, periodontomas

- Periodontitis

- Periodontitis in remission

- Periodontosis

- Severe chronic generalized periodontitis

- Ulcerative gingivitis