Trigeminal neuralgia

- Understanding Trigeminal Neuralgia (Tic Douloureux)

- Diagnosis of Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia

- General Principles and Initial Management

- Pharmacological Treatment (Medication)

- Surgical and Interventional Treatments

- Adjunctive Therapies (Acupuncture, Physiotherapy)

- Differential Diagnosis of Facial Pain

- Prognosis and Complications

- When to Consult a Specialist (Neurologist, Neurosurgeon)

- References

![]() Attention! Please do not confuse the diagnosis of "trigeminal neuralgia" (characterized by severe, paroxysmal facial pain) as described in this article with the distinct diagnoses of "trigeminal neuropathy" (typically involving sensory loss/paresthesia and/or weakness of mastication) or "facial nerve neuropathy/neuritis" (causing facial muscle weakness/paralysis).

Attention! Please do not confuse the diagnosis of "trigeminal neuralgia" (characterized by severe, paroxysmal facial pain) as described in this article with the distinct diagnoses of "trigeminal neuropathy" (typically involving sensory loss/paresthesia and/or weakness of mastication) or "facial nerve neuropathy/neuritis" (causing facial muscle weakness/paralysis).

Understanding Trigeminal Neuralgia (Tic Douloureux)

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN), historically known as tic douloureux, is a chronic pain disorder affecting the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The hallmark symptom is recurrent episodes of intense, stabbing, electric shock-like (paroxysmal) pain in the sensory distribution of one or more branches of this nerve on one side of the face. The pain in trigeminal neuralgia often reaches an excruciating degree, significantly impacting the patient's quality of life.

Definition and Clinical Characteristics

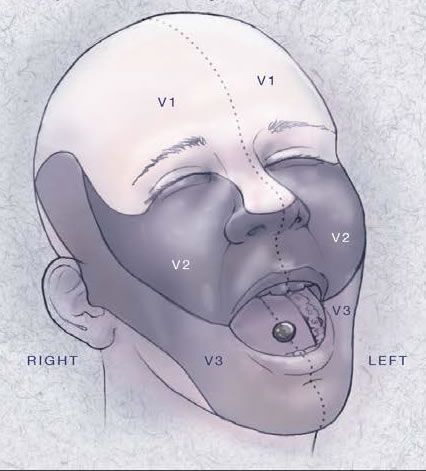

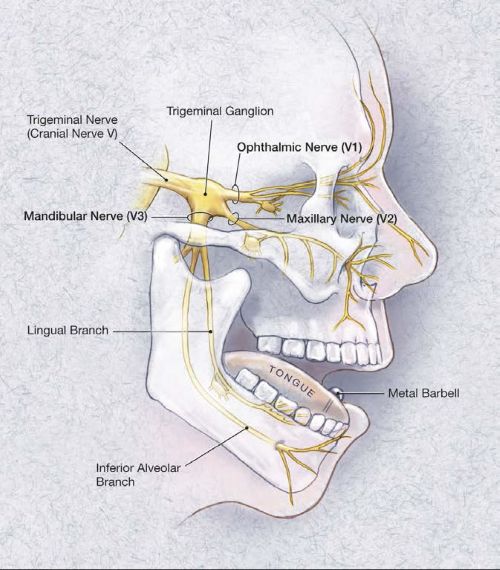

The trigeminal nerve has three main branches: ophthalmic (V1), maxillary (V2), and mandibular (V3), supplying sensation to the face, oral cavity, nasal cavity, and motor function to the muscles of mastication. TN pain typically follows the distribution of one or more of these branches.

Associated Symptoms and Trigger Zones

Often, during an attack of pain in trigeminal neuralgia, associated **autonomic (vegetative) symptoms** may be observed on the affected side of the face. These can include:

- Localized sweating (hyperhidrosis).

- Facial redness (flushing) or swelling (edema).

- Lacrimation (tearing).

- Increased salivation.

- Nasal congestion or rhinorrhea.

Sometimes with trigeminal neuralgia, painful convulsive twitching of the facial muscles (**tic douloureux**) occurs with clonic (jerky) contractions on the affected side during a pain paroxysm.

In the intervals between acute attacks of trigeminal neuralgia, the patient may be completely pain-free or experience a mild, dull residual ache. A characteristic feature of TN is the presence of **trigger zones** – specific areas on the face or inside the mouth where innocuous stimuli (such as light touch, washing the face, shaving, brushing teeth, talking, eating, or even a cool breeze) can provoke an excruciating attack of pain. Patients often become wary of touching or stimulating these zones, leading to guarded movements and avoidance behaviors (e.g., difficulty eating, poor oral hygiene).

Etiology: Symptomatic vs. Idiopathic (Essential) Forms

Trigeminal neuralgia can be classified based on its underlying cause:

- Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia (often historically termed Idiopathic or Essential TN): This is the most common form. It is now largely understood to be caused by **neurovascular compression**, where a blood vessel (usually an artery, sometimes a vein) compresses the trigeminal nerve root at its entry zone into the brainstem (pons). This chronic pulsatile compression is thought to lead to focal demyelination and ectopic nerve impulse generation, resulting in the characteristic pain attacks. In many cases previously termed idiopathic, an inflammatory etiology or subtle compressive factor might have been present but unidentifiable with older diagnostic methods.

- Symptomatic Trigeminal Neuralgia (Secondary TN): In these cases, the neuralgia is a manifestation of an identifiable underlying pathological process that directly irritates or damages the trigeminal nerve or its pathways. Such processes can be localized:

- Intracranially (e.g., tumors like acoustic neuromas, meningiomas, epidermoid cysts in the cerebellopontine angle or Meckel's cave; vascular malformations; multiple sclerosis plaques affecting the trigeminal pathways in the brainstem).

- Within the cranial cavity or skull base.

- Extracranially in tissues adjacent to peripheral nerve branches (e.g., inflammatory processes of the paranasal sinuses, diseases of the teeth and jaws, basal skull lesions).

Diagnosis of Trigeminal Neuralgia

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is primarily based on the characteristic clinical history of paroxysmal facial pain. A thorough neurological examination is performed to rule out sensory deficits or other neurological signs that might suggest symptomatic TN or an alternative diagnosis. Imaging is crucial to exclude secondary causes.

- Clinical Criteria: Based on the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) criteria, including recurrent paroxysms of unilateral facial pain, lasting from a fraction of a second to two minutes, affecting one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve, with pain having characteristics such as severe intensity, electric shock-like, shooting, stabbing, or sharp quality, and often precipitated by innocuous stimuli within the affected trigeminal distribution.

- Neurological Examination: Usually normal in classical TN between attacks, although mild sensory changes can sometimes be found. Significant sensory loss, weakness of mastication, or other cranial nerve deficits point towards symptomatic TN.

- Imaging (MRI): High-resolution MRI of the brain with specific sequences (e.g., FIESTA, CISS, 3D TOF-MRA) is essential to look for neurovascular compression at the trigeminal root entry zone and to rule out secondary causes like tumors, multiple sclerosis plaques, or vascular malformations.

- Electrodiagnostic Tests: Trigeminal reflexes (e.g., blink reflex) or trigeminal evoked potentials may show abnormalities but are not routinely used for diagnosis unless atypical features are present.

Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia

With symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia, treatment efforts must be directed at eliminating or managing the underlying disease (e.g., tumor resection, treatment of MS). In cases of unclear etiology or when an inflammatory nature is suspected (though less common for classical TN), initial management often involves pharmacological and physiotherapeutic approaches.

Surgical and interventional methods for treating trigeminal neuralgia are aimed at interrupting the pain pathways or decompressing the nerve root and can be broadly divided into extracranial and intracranial procedures.

Pharmacological Treatment (Medication)

Medical therapy is the first-line treatment for trigeminal neuralgia.

- Anticonvulsants:

- Carbamazepine (e.g., Tegretol, Finlepsin): The most effective and commonly used medication, often providing significant pain relief.

- Oxcarbazepine: Similar to carbamazepine, may have fewer side effects for some patients.

- Other anticonvulsants like gabapentin, pregabalin (Lyrica), lamotrigine, phenytoin, or baclofen (a muscle relaxant) may be used as alternatives or adjuncts if carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine are ineffective or not tolerated.

- Other Medications:

- Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline) can sometimes help with neuropathic pain.

- Suksilep (ethosuximide, primarily an anti-absence seizure medication) was historically mentioned but is not a standard treatment for TN.

It should be pointed out that as new and more effective medications are developed and proposed, the indications for surgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia in some patients are decreasing, or surgery is deferred until medical options are exhausted.

Surgical and Interventional Treatments

For patients with drug-resistant trigeminal neuralgia (estimated at 25-50% who eventually stop responding to pain medication) or those who cannot tolerate medications, various surgical or interventional procedures are available to relieve suffering. Different surgical methods have both advantages and limitations.

Percutaneous Procedures (Historical and Modern)

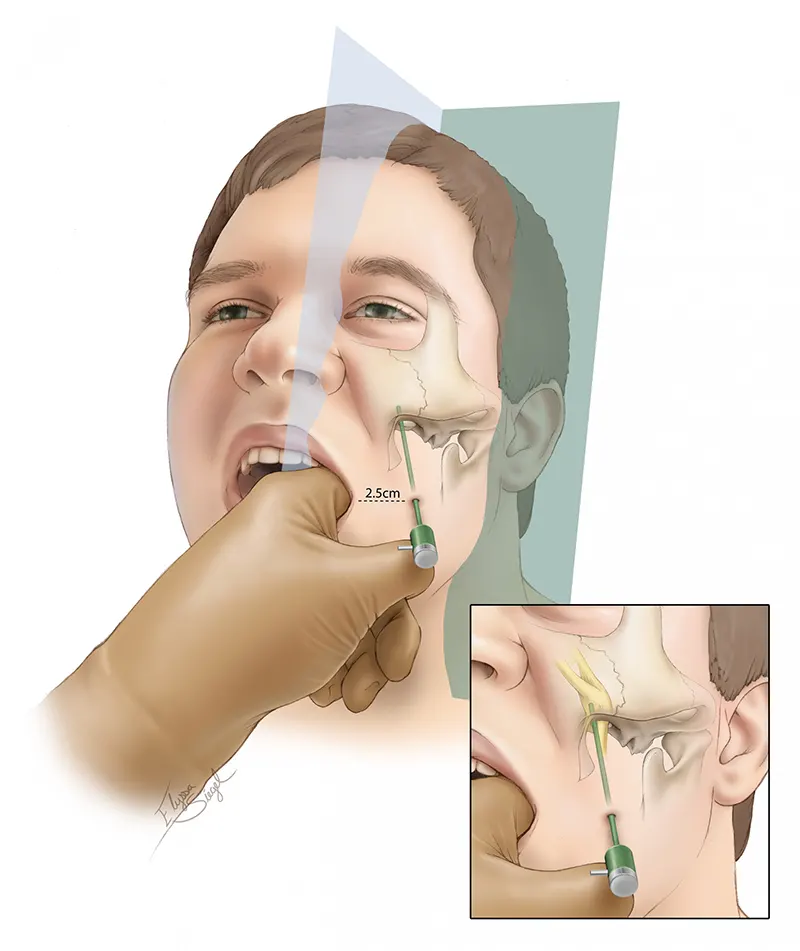

These procedures target peripheral branches or the Gasserian (trigeminal) ganglion via a needle inserted through the cheek, typically through the foramen ovale.

- Peripheral Nerve Blocks/Neurolysis (Extracranial):

- Transection (Neurotomy) or Avulsion (Neuroexeresis) of Peripheral Trigeminal Branches: Historically, operations involving cutting (neurotomy) or twisting and pulling out (neuroexeresis) peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve (e.g., supraorbital, infraorbital, mental nerves) were performed. Neurotomy is easily performed and can stop pain, but nerve regeneration often occurs relatively quickly, leading to recurrence of pain. Neuroexeresis, excising a 2-4 cm section of the peripheral branch, provided longer relief (typically 6-12 months) but pain usually returned. Attempts to prevent regeneration by filling bony foramina (through which branches pass) with materials like wood, bone, metal pins, muscle, wax, or paraffin often did not lead to persistent recovery, with pain relapses frequently occurring.

Access to V1 branches was via a medial supraorbital incision. The infraorbital nerve (V2) could be accessed extraorally (incision below inferior orbital rim, taking care to avoid facial nerve branches to lower eyelid) or intraorally (incision below transitional fold from canine to first molar, exposing nerve after elevating mucosa and periosteum). The mental nerve (V3) was accessed intraorally (incision from canine to first molar, 0.5-0.75 cm below gingival margin). Most neurosurgeons now view these peripheral destructive procedures negatively for classical TN due to high recurrence rates and prefer targeting the ganglion or root.

- Alcoholization (Chemical Neurolysis): Intraneural injection of 1-2 ml of 80% alcohol with novocaine (procaine) into the nerve trunk or its branches to achieve a chemical blockade. This was often performed on an outpatient basis and could provide pain relief for 0.5-1 year or more, after which repeat alcoholization could be done. Results were best for V2 and V3 neuralgia, less effective for V1. While seemingly simple, precise targeting requires skill, and alcohol can spread, risking damage to adjacent structures. Adhesions could also form, complicating later intracranial surgery. Deep alcohol injections near the foramen ovale/rotundum were technically demanding.

- Transection (Neurotomy) or Avulsion (Neuroexeresis) of Peripheral Trigeminal Branches: Historically, operations involving cutting (neurotomy) or twisting and pulling out (neuroexeresis) peripheral branches of the trigeminal nerve (e.g., supraorbital, infraorbital, mental nerves) were performed. Neurotomy is easily performed and can stop pain, but nerve regeneration often occurs relatively quickly, leading to recurrence of pain. Neuroexeresis, excising a 2-4 cm section of the peripheral branch, provided longer relief (typically 6-12 months) but pain usually returned. Attempts to prevent regeneration by filling bony foramina (through which branches pass) with materials like wood, bone, metal pins, muscle, wax, or paraffin often did not lead to persistent recovery, with pain relapses frequently occurring.

- Gasserian Ganglion Procedures (Puncture Access): In severe forms of trigeminal neuralgia, after unsuccessful attempts at drug and physiotherapeutic treatment, and failure of extracranial nerve blocks, indications for intracranial operations or percutaneous procedures targeting the Gasserian (trigeminal) ganglion or nerve root arise. These are performed by inserting a needle through the skin of the face (typically via the Hartel anterior approach) through the foramen ovale into Meckel's cave, where the ganglion resides.

- Glycerol Rhizotomy: Injection of sterile glycerol into the trigeminal cistern to damage pain fibers.

- Radiofrequency Thermocoagulation (RFT) / Rhizotomy: Using heat generated by radiofrequency current, delivered via an electrode passed through the needle, to create a controlled thermal lesion in the Gasserian ganglion or nerve root, selectively damaging pain-transmitting fibers. For patients with trigeminal neuralgia, percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy is often performed with mild sedation. (Kirshner, 1931, first applied electrocoagulation of the Gasserian ganglion via foramen ovale puncture. Schmechel, 1951, reported good results in 118 patients. Heness, 1957, recommended it for elderly patients, reporting 62.5% recovery in 171 patients with no deaths; only 25 later required intracranial surgery).

- Balloon Microcompression: A Fogarty-type balloon catheter is inserted through the needle into Meckel's cave and inflated to compress the Gasserian ganglion and nerve root, disrupting pain fibers.

- Historical: Injection of alcohol or hot water into the Gasserian ganglion/trigeminal cistern: Novocaine or alcohol injections directly into the Gasserian ganglion often gave good results, but risked damage to adjacent brain structures due to alcohol spread. Hot water injection for hydrothermal destruction of the sensory root was also used. These methods are largely obsolete due to higher complication rates and less controlled lesions compared to RFT or glycerol.

Even after a safely performed alcohol injection into the Gasserian ganglion, adhesions could form, posing significant difficulties for neurosurgeons if subsequent intracranial surgery became necessary.

Intracranial Surgical Approaches (Historical Context and Evolution)

In the historical development of trigeminal neuralgia treatment, interventions progressively moved from the periphery towards the central nervous system.

- Gasserian Ganglion Removal (Extirpation - Historical): The idea of removing the Gasserian ganglion for severe TN was implemented by Rose (1890), who, after resecting the upper jaw, accessed the foramen ovale and scraped out the ganglion in parts. This was difficult and non-radical. Hartley (1882) and Krause (1882) described an intracranial temporal approach for Gasserian ganglion removal. After osteoplastic trepanation of the temporal bone, detachment of the dura mater from the middle cranial fossa base, and elevation of the temporal lobe, ample access to the ganglion could be obtained. However, ganglion extirpation, while effective for pain, was a difficult and dangerous intervention (due to proximity to cavernous sinus) and is no longer used.

- Retrogasserian Sensory Root Section (Spiller-Frazier Operation - Historical Standard): This operation replaced ganglionectomy. First successfully performed by Spiller and Frazier (1901), it involved transecting the sensory root of the trigeminal nerve just posterior to the Gasserian ganglion. Based on experiments showing no regeneration after dorsal root transection, this became a safer and reliable method. The procedure involves a small temporal trepanation, extradural elevation of the temporal lobe dura to reach Meckel's cave, opening the capsule, and cutting the sensory portion of the trigeminal root while attempting to preserve its motor part. Frazier found that fibers from the three divisions run somewhat separately in the root. Improvements included preserving the motor root and performing partial transection of the sensory root (sparing V1 fibers if not involved, to prevent neuroparalytic keratitis). Total root transection led to keratitis in ~16.7%, while partial transection reduced this to ~4.4%. Pain relapses occurred in 5-18%. Paresthesias in the anesthetized area were common (10-20%). An intradural temporal approach was also proposed to avoid complications associated with extradural manipulation but carried its own risks.

- Suboccipital Sensory Root Section (Dandy Operation - Historical): Transection of the sensory trigeminal nerve root directly at the pons, via a posterior cranial fossa approach, was first successfully performed by Dandy (1925). He emphasized advantages like potential preservation of tactile sensation while abolishing pain, reducing unpleasant numbness. Dandy reported good results with low mortality in later series. However, other authors reported higher mortality (3-5%) compared to the temporal approach (0.8-1.9%).

- Decompression of Gasserian Ganglion/Root (Taarnhøj Procedure - Historical): Taarnhøj (1952) proposed that pain in TN might be due to compression of the root or ganglion, even by subtle vascular or inflammatory changes within the dural canal near the petrous ridge. He reported pain relief after simple "decompression" involving wide dissection of the dura mater over the ganglion and root, and widening the dural opening at the tentorial edge. Love and Svien (1954) reported mixed results with this operation at the Mayo Clinic: 50% immediate success, but 31% relapsed within 1-22 months.

- Bulbospinal Tractotomy (Sjöqvist Operation - Historical): Based on Koontz's anatomical proposal (1931) to cut the descending (spinal) tract of the trigeminal nerve in the medulla oblongata to abolish pain while preserving facial touch and motor function. Burdenko (1936) proved the feasibility of bulbar tractotomy in humans for hyperkinesis. Sjöqvist (1937) first performed tractotomy for TN, incising the sensory trigeminal tract on the lateral surface of the medulla oblongata, near the inferior angle of the 4th ventricle. Summary statistics showed 1.5% mortality and a high relapse rate (37%), making it less favorable than retrogasserian root section. Sjöqvist himself later considered it more indicated for V1 neuralgia in young people (to avoid permanent tactile anesthesia), TN with MS, and contraindicated for V3 neuralgia due to unreliable anesthesia.

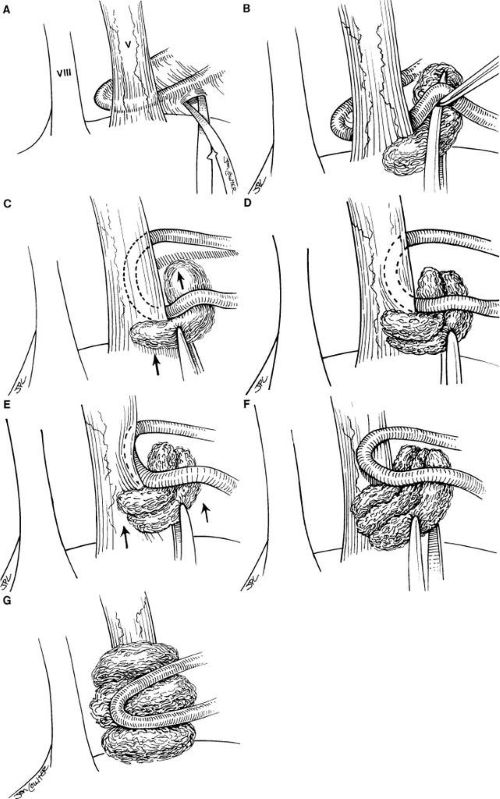

Modern Standard: Microvascular Decompression (MVD)

Microvascular decompression (MVD) of the trigeminal nerve root at its exit zone in the cerebellopontine angle is recognized today as the surgical procedure offering the most durable pain relief for classical trigeminal neuralgia caused by neurovascular compression. The operation is performed via a retrosigmoid (suboccipital) craniectomy (behind the auricle). Under microscopic visualization, the compressing blood vessel (usually an artery) is identified and gently mobilized away from the nerve root, and a small inert Teflon felt sponge is interposed to prevent recurrent compression.

Thus, current major surgical approaches targeting the intracranial sections of the trigeminal system include:

- Percutaneous procedures targeting the Gasserian ganglion/root in the middle cranial fossa (e.g., RFT, glycerol rhizotomy, balloon microcompression).

- Microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve root in the posterior cranial fossa.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery.

Older, more destructive intracranial procedures like Gasserian ganglionectomy or open root sections are largely historical.

Stereotactic Radiosurgery (e.g., Gamma Knife)

This non-invasive technique delivers a highly focused beam of radiation to the trigeminal nerve root. It is an option for patients who are not good surgical candidates for MVD or who prefer a less invasive approach. Pain relief is often delayed by several weeks to months and may be less complete or durable than MVD, with a higher chance of sensory loss.

Adjunctive Therapies

- Acupuncture: Considered a complementary treatment for trigeminal neuralgia, potentially offering pain relief for some individuals.

- Physiotherapy: May include TENS, relaxation techniques, or exercises to manage facial muscle tension or guarding, but primarily addresses secondary effects rather than the neuralgia itself. Physiotherapy can help accelerate the elimination of burning pain on the skin of the face and teeth.

- Psychological Support: Given the severity and chronic nature of TN pain, psychological support, counseling, or cognitive-behavioral therapy can be very important for coping and quality of life.

Differential Diagnosis of Facial Pain

Trigeminal neuralgia must be differentiated from other causes of facial pain:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN) | Paroxysmal, electric shock-like, severe unilateral pain in V1, V2, or V3 distribution; trigger zones; pain-free intervals (initially). Neurological exam usually normal. Responds to carbamazepine. |

| Symptomatic Trigeminal Neuralgia | Similar pain to classical TN, but caused by an identifiable lesion (tumor, MS plaque, vascular malformation). May have associated sensory loss or other neurological signs. MRI crucial. |

| Post-Traumatic Trigeminal Neuropathy | History of facial/dental trauma or surgery. Often persistent pain (burning, aching) and/or sensory loss (numbness, paresthesia) in a trigeminal branch distribution. |

| Dental Pain (Pulpitis, Abscess, Cracked Tooth) | Pain localized to a tooth, often throbbing, sensitive to temperature or percussion. Dental examination and imaging are key. Can radiate. |

| Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Dysfunction | Pain in jaw joint, ear, or preauricular area, often with clicking, popping, or limited jaw movement. Tenderness of masticatory muscles. |

| Acute Sinusitis (Maxillary, Frontal, Sphenoid) | Facial pain/pressure over affected sinus, nasal congestion/discharge, fever. CT of sinuses diagnostic. Pain usually dull, constant. |

| Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus/Maxillaris/Mandibularis (Shingles) | Vesicular rash in a trigeminal dermatome, followed by acute pain (herpetic neuralgia) and potentially persistent postherpetic neuralgia. |

| Migraine or Cluster Headache with Facial Pain | Headache is primary. Migraine often unilateral, throbbing, with nausea/photophobia/aura. Cluster headache severe, orbital/periorbital, with autonomic signs (tearing, nasal congestion). |

| Atypical Facial Pain / Persistent Idiopathic Facial Pain | Chronic, often constant, poorly localized facial pain, may not follow clear nerve distribution. May be burning or aching. No objective neurological deficits. Diagnosis of exclusion. |

| Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia | Paroxysmal pain in throat, tonsil, ear, base of tongue, triggered by swallowing/talking. Can sometimes be confused with V3 TN. |

Prognosis and Complications

Trigeminal neuralgia is typically a chronic condition with a relapsing-remitting course. While not life-threatening itself, the severe pain can be debilitating.

- Medical Treatment: Many patients achieve good pain control with medications, but effectiveness can wane over time, or side effects may become intolerable.

- Surgical/Interventional Treatment:

- Microvascular decompression (MVD) offers the highest rate of long-term pain relief but is an open intracranial surgery with associated risks.

- Percutaneous procedures (RFT, glycerol, balloon compression) are less invasive but have higher recurrence rates and a greater chance of causing facial numbness or other sensory disturbances.

- Stereotactic radiosurgery provides non-invasive treatment, but pain relief is often delayed and may not be as complete or durable.

Complications can arise from the disease itself (e.g., weight loss due to pain with eating, depression, social isolation) or from its treatment (e.g., medication side effects, anesthesia dolorosa - painful numbness after destructive procedures, facial sensory loss, corneal anesthesia with V1 involvement leading to keratitis, motor weakness if V3 motor root damaged).

When to Consult a Specialist (Neurologist, Neurosurgeon)

Individuals experiencing symptoms suggestive of trigeminal neuralgia should consult a physician, typically a neurologist, for an accurate diagnosis and initial management. Referral to a neurosurgeon or pain management specialist experienced in treating trigeminal neuralgia is often necessary if:

- The diagnosis is confirmed and medical management is being considered or initiated.

- Pain is not adequately controlled with medications, or side effects are intolerable.

- Surgical or interventional treatment options are being considered.

- There are atypical features or neurological deficits suggesting a possible secondary cause (symptomatic TN) that requires further investigation or specific treatment.

Early and accurate diagnosis, followed by a tailored treatment plan, can significantly improve the quality of life for patients with trigeminal neuralgia.

References

- Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia: New classification and diagnostic grading for practice and research. Neurology. 2016 Jul 12;87(2):220-8.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018 Jan;38(1):1-211. (Section on Trigeminal Neuralgia).

- Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia--pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2001 Jul;87(1):117-32.

- Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ. 2014 Jul 7;348:g474.

- Burchiel KJ. A new classification for facial pain. Neurosurgery. 2003 Nov;53(5):1164-6; discussion 1166-7.

- Tatli M, Satici O, Kanpolat Y, Sindou M. Various surgical modalities for trigeminal neuralgia: literature review of respective long-term outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008 Mar;150(3):243-55.

- Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 2001 Dec;124(Pt 12):2347-60.

- Jannetta PJ. Arterial compression of the trigeminal nerve at the pons in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1967 Jan;26(1):Suppl:159-62. (Seminal paper on MVD).

- Dalessio DJ. Medical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin Neurosurg. 1982;29:496-503. (Historical context on medical treatment).

See also

- Anatomy of the nervous system

- Spinal disc herniation

- Pain in the arm and neck (trauma, cervical radiculopathy)

- The eyeball and the visual pathway:

- Anatomy of the eye and physiology of vision

- The visual pathway and its disorders

- Eye structures and visual disturbances that occur when they are affected

- Retina and optic disc, visual impairment when they are affected

- Impaired movement of the eyeballs

- Nystagmus and conditions resembling nystagmus

- Dry Eye Syndrome

- Optic nerve and retina:

- Compression neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Edema of the optic disc (papilledema)

- Ischemic neuropathy of the optic nerve

- Meningioma of the optic nerve sheath

- Optic nerve atrophy

- Optic neuritis in adults

- Optic neuritis in children

- Opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis

- Pseudo-edema of the optic disc (pseudopapilledema)

- Toxic and nutritional optic neuropathy

- Neuropathies and neuralgia:

- Diabetic, alcoholic, toxic and small fiber sensory neuropathy (SFSN)

- Facial nerve neuritis (Bell's palsy, post-traumatic neuropathy)

- Fibular (peroneal) nerve neuropathy

- Median nerve neuropathy

- Neuralgia (intercostal, occipital, facial, glossopharyngeal, trigeminal, metatarsal)

- Post-traumatic neuropathies

- Post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

- Post-traumatic sciatic nerve neuropathy

- Radial nerve neuropathy

- Tibial nerve neuropathy

- Ulnar nerve neuropathy

- Tumors (neoplasms) of the peripheral nerves and autonomic nervous system (neuroma, sarcomatosis, melanoma, neurofibromatosis, Recklinghausen's disease)

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar nerve compression in the cubital canal

anatomy (trigeminal ganglion and branches).webp)

block.webp)