Hydrocele

- Understanding Hydrocele (Dropsy of the Testicle)

- Acute Hydrocele (Acute Periorchitis)

- Chronic Hydrocele

- Diagnosis of Hydrocele

- Potential Complications of Hydrocele

- Treatment of Hydrocele

- Differential Diagnosis of Scrotal Swelling

- Prevention of Complications and When to Consult a Urologist

- References

Understanding Hydrocele (Dropsy of the Testicle)

A hydrocele is defined as an abnormal accumulation of serous (clear) fluid within the potential space between the parietal and visceral layers of the tunica vaginalis, the serous membrane that envelops the testicle. This condition is sometimes referred to by the older layman's term "dropsy of the testicle." Hydroceles can be either congenital (present at birth or developing in early infancy) or acquired (developing later in life).

Some historical texts associated the appearance of hydrocele with prolonged physical labor or specific occupational activities like frequent horseback riding (common in riders) or driving vehicles (in chauffeurs), suggesting these might contribute to its development, though modern understanding focuses more on underlying anatomical or pathological factors causing an imbalance in fluid production and absorption.

Definition and Pathophysiology

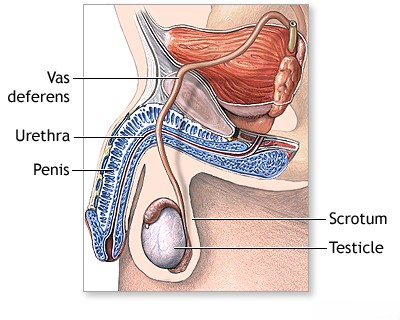

The tunica vaginalis is a remnant of the processus vaginalis, an outpouching of peritoneum that accompanies the testis during its descent into the scrotum. Normally, a small amount of lubricating serous fluid is present between its two layers. A hydrocele forms when there is an excessive production of this fluid, impaired absorption of the fluid, or (in congenital cases) a communication with the peritoneal cavity allowing abdominal fluid to enter the scrotal sac.

Types of Hydroceles: Congenital vs. Acquired

- Congenital Hydrocele:

- Communicating Hydrocele: This type results from a failure of the processus vaginalis to completely obliterate (close off) after testicular descent. This leaves a patent (open) connection between the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity and the tunica vaginalis sac in the scrotum. Peritoneal fluid can then freely move into the scrotum, causing the hydrocele size to fluctuate (e.g., larger when active, smaller when resting or in the morning). This type is common in newborns and often resolves spontaneously within the first year or two of life.

- Non-communicating Hydrocele (Infantile Hydrocele): In this type, the processus vaginalis is closed off at the internal inguinal ring (preventing communication with the abdomen), but fluid remains trapped within the tunica vaginalis around the testis and sometimes a portion of the spermatic cord.

- Acquired Hydrocele: This type develops later in life, typically in adult men, due to various underlying causes that disrupt the balance of fluid secretion and absorption by the tunica vaginalis. Common causes include:

- Inflammation or infection of the testis (orchitis) or epididymis (epididymitis).

- Trauma to the scrotum or testicle.

- Testicular tumors (though rare, a reactive hydrocele can occur).

- Complications of surgery (e.g., varicocelectomy, hernia repair).

- Radiation therapy to the pelvic area.

- Idiopathic (unknown cause), particularly in older men.

Anatomical Variations of Hydroceles

The physical presentation of a hydrocele can vary based on its extent and anatomical configuration:

- Testicular Hydrocele: The fluid accumulation is confined to the tunica vaginalis surrounding the testicle itself, typically resulting in an ovoid or egg-shaped scrotal swelling.

- Hydrocele of the Spermatic Cord (Funicular Hydrocele): Fluid accumulates within an unobliterated segment of the processus vaginalis along the spermatic cord, separate from the tunica vaginalis of the testis.

- Encysted Hydrocele of the Cord: A localized, non-communicating fluid collection along the cord.

- Pear-Shaped Hydrocele: With increasing fluid volume, a testicular hydrocele can extend upwards involving the sheaths of the spermatic cord, giving the entire swelling a pear shape with the narrow end (apex) directed towards the inguinal canal.

- Hourglass Hydrocele (Abdominoscrotal or Bilocular Hydrocele): This occurs when there are cicatricial (scar tissue) constrictions along the spermatic cord (either congenital or acquired), or when a large communicating hydrocele has both scrotal and abdominal components. The hydrocele takes on an hourglass shape: one sac is within the scrotum, and the other (inner sac) is located more proximally, such as under the skin in the inguinal canal region, or even extending into the abdominal cavity if communicating through an unsealed processus vaginalis.

- Multi-chambered (Multiloculated) Hydrocele: Can form in the presence of inflammatory adhesions or septations between the two layers of the tunica vaginalis, dividing the fluid collection into multiple compartments.

Clinically, hydroceles are often categorized into acute and chronic forms based on their onset and duration.

Acute Hydrocele (Acute Periorchitis)

Causes and Clinical Presentation

Acute hydrocele, sometimes termed acute periorchitis (inflammation of the tissues surrounding the testis), typically develops relatively rapidly over several days. It may persist in a stable state for 1-2 weeks and can subsequently resolve completely without residual effects or transition into a chronic hydrocele. Acute hydrocele is usually a **reactive phenomenon**, occurring secondary to an underlying acute inflammatory process or trauma involving the scrotal contents.

Clinical features of acute hydrocele include:

- Rapid Onset Scrotal Swelling: A noticeable, often tender, swelling of one half of the scrotum.

- Pain and Tenderness: The affected scrotum is usually very sensitive or painful to touch.

- Skin Changes: The overlying scrotal skin may exhibit diffuse redness (erythema) and signs of edema(swelling).

- Consistency and Fluctuation: The scrotal swelling is typically elastic and clearly demonstrates fluctuation (a wave-like motion indicative of fluid can be elicited on palpation).

- Percussion: Yields a dull sound over the fluid-filled area.

- Transillumination: The swelling usually transilluminates brightly when a light source is shone through it, confirming the presence of clear fluid.

- Testicle Palpation: It is often difficult or impossible to distinctly palpate the testicle, as it is typically surrounded by and may be pushed posteriorly by the accumulated fluid.

- Systemic Symptoms: An acute hydrocele is frequently accompanied by systemic signs of inflammation, such as a significant increase in body temperature (fever).

The most common causes of acute hydrocele are traumatic injury to the scrotum or an acute inflammatory process affecting the epididymis (epididymitis) or the testicle itself (orchitis).

Chronic Hydrocele

Development and Symptoms

Chronic hydrocele usually develops gradually, often over months or years, and may cause little or no discomfort to the patient in its early stages. Symptoms typically become noticeable when the hydrocele reaches a considerable size, causing:

- Painless Scrotal Swelling: This is the most common presentation. The swelling is usually smooth, ovoid or pear-shaped.

- Scrotal Heaviness or Dragging Sensation: Due to the weight and bulk of the fluid collection.

- Discomfort: Pain in the groin or scrotal discomfort may occur, particularly with large hydroceles or during physical activity.

- Interference with Activities: Discomfort during sexual intercourse, walking, or other physical movements.

- Urinary Issues (Rare): In cases of very large chronic hydroceles, the penis may be retracted into the scrotal mass ("buried penis"), which can alter the direction of the urine stream. This, in turn, can lead to urine consistently moisturizing the scrotal skin, potentially causing secondary skin irritation or eczema.

Clinically, a chronic hydrocele typically presents as a pear-shaped or ovoid scrotal swelling. The upper border of the swelling is usually well-defined and can be palpated separately from any inguinal hernia (i.e., one can "get above" the swelling). The scrotal skin over small hydroceles often appears normal; with large hydroceles, the skin can be thinned and stretched but typically remains mobile over the underlying sac. The consistency of the swelling depends on the amount of fluid and the tension within the sac: it can range from soft and fluctuant to sharply tense, like a dense elastic formation. In tense hydroceles, it may be impossible to palpate the testicle and epididymis within it. If the fluid tension is slight, the testicle and epididymis are often palpable, typically displaced posteriorly and inferiorly within the sac.

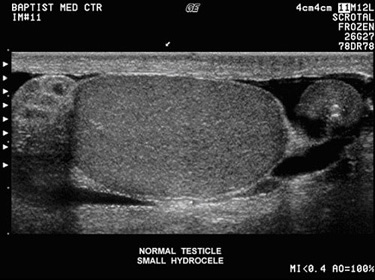

Percussion of the swelling in chronic hydrocele yields a dull sound. A characteristic diagnostic sign is **transillumination**: when a bright light source (e.g., a penlight or otoscope light) is held firmly against one surface of the scrotal swelling in a darkened room, the light will pass through the clear serous fluid, causing the entire hydrocele sac to glow or appear translucent. This helps to differentiate a hydrocele from solid scrotal masses (e.g., testicular tumors, hematoceles) or hernias containing bowel, which do not transilluminate. However, if the tunica vaginalis is significantly thickened due to chronic inflammation or previous procedures, or if the hydrocele fluid is cloudy or contains blood, transillumination may be reduced or absent.

In a **communicating hydrocele** (which typically follows a chronic course, though it originates congenitally), the scrotal swelling characteristically fluctuates in size. It may appear or increase in size when the patient is walking, standing, or straining (Valsalva maneuver), and can decrease or disappear entirely or in part when the patient is in a supine (lying down) position, as the fluid drains back into the peritoneal cavity.

Prognosis of Chronic Hydrocele

The prognosis for acute hydroceles, if the underlying cause is treated, is generally favorable, with many resolving. For chronic hydroceles, especially in adults, spontaneous cure is uncommon, and intervention is often required if they are symptomatic, large, or causing concern. In children with communicating hydroceles, spontaneous obliteration of the patent processus vaginalis and resolution of the hydrocele can sometimes occur, particularly within the first 1 to 2 years of life. If persistence occurs beyond this age, surgical intervention is usually considered.

Diagnosis of Hydrocele

The diagnosis of a hydrocele is primarily clinical, based on history and physical examination, often confirmed by imaging.

- Clinical History: Onset and duration of swelling, presence of pain or discomfort, history of trauma, infection, or previous scrotal surgery. In infants, history of prematurity or other congenital anomalies.

- Physical Examination:

- Inspection of the scrotum for size, shape, and skin changes.

- Palpation to assess consistency (fluctuant, tense), ability to get above the swelling (differentiates from hernia), and to attempt palpation of the testis and epididymis.

- Transillumination: A key diagnostic maneuver. Shining a bright light through the scrotum will illuminate a hydrocele due to its fluid content. Solid masses or hernias containing bowel will not transilluminate.

- Scrotal Ultrasound: This is the most important imaging study. It definitively confirms the presence of fluid within the tunica vaginalis, characterizes the fluid (simple or complex), accurately assesses the volume, and, crucially, allows for detailed evaluation of the underlying testis and epididymis to rule out associated pathology such as tumors, inflammation, or torsion, which might be causing a reactive hydrocele.

- Laboratory Tests: Generally not required for uncomplicated hydroceles. If infection is suspected (e.g., acute hydrocele with fever), a complete blood count (CBC) and urinalysis may be performed. Tumor markers (AFP, β-hCG, LDH) are indicated if a testicular tumor is suspected on ultrasound.

Potential Complications of Hydrocele

While many hydroceles are benign and cause minimal issues, potential complications can arise, especially if they are large, tense, or long-standing:

- Infection of the Hydrocele Fluid (Pyocele): This can occur spontaneously (though rare) or exogenously as a result of diagnostic or therapeutic aspiration (puncture). It leads to a painful, inflamed scrotum with systemic signs of infection.

- Hemorrhage into the Hydrocele Sac (Hematocele): Bleeding into the tunica vaginalis, often due to trauma or following aspiration. The swelling becomes firm, painful, and does not transilluminate.

- Rupture of the Hydrocele Sac: Can occur due to direct trauma (though spontaneous ruptures have been anecdotally observed, possibly due to loss of membrane elasticity from chronic inflammation). The risk might be higher with rapidly enlarging hydroceles. The specific location of the rupture is not always definite.

- Testicular Atrophy: Although uncommon, very large and tense hydroceles might theoretically impair testicular blood supply or thermoregulation, potentially leading to testicular damage or atrophy over time.

- Discomfort and Interference with Daily Activities: Large hydroceles can be heavy, cumbersome, and cause cosmetic embarrassment or interfere with physical activity and sexual function.

- Inguinal Hernia: In cases of communicating hydroceles, the patent processus vaginalis that allows fluid passage can also permit herniation of abdominal contents (bowel, omentum) into the scrotum.

- Skin Problems: Chronic irritation from a large, dependent scrotum or moisture from altered urination can lead to scrotal skin eczema or maceration.

Prevention of complications associated with hydrocele, particularly infection or trauma, involves general scrotal care. Historically, wearing a suspensory was advised for any disease of the genitourinary system, including hydrocele, to provide support and potentially reduce discomfort or risk of injury, though this is not a curative measure.

Treatment of Hydrocele

Conservative Management and Observation

Conservative treatment is primarily indicated for **acute hydroceles** that are reactive to an underlying inflammatory condition such as epididymitis or orchitis. Management focuses on treating the primary cause (e.g., with antibiotics), providing scrotal support, rest, analgesics, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Application of warming compresses to the scrotum was a historical suggestion, though for acute inflammation, ice packs might be preferred initially.

For **congenital communicating hydroceles** in infants, observation is the standard initial approach. Many of these resolve spontaneously within the first 12 to 18 months of life as the processus vaginalis gradually closes. Surgical intervention is typically considered if the hydrocele persists beyond this age, is very large, tense, associated with a clinically apparent inguinal hernia, or causes discomfort.

Asymptomatic, small, stable chronic hydroceles in adults may not require any specific treatment other than reassurance and periodic monitoring.

Surgical Interventions (Hydrocelectomy Techniques)

Operative treatment (hydrocelectomy) is generally indicated for chronic symptomatic hydroceles in adults, large or persistent hydroceles in children beyond the age of expected spontaneous resolution, or if complications such as infection or significant discomfort arise. The goal of surgery is to either remove the hydrocele sac or to alter its anatomy to prevent further fluid accumulation. Several established "radical" surgical techniques exist, typically performed through a scrotal or inguinal incision:

- Lord's Plication: This technique is suitable for hydroceles with thin, pliable sacs. After a longitudinal incision through all layers of the scrotum down to the serous membrane of the testicle (tunica vaginalis), without incising it initially, the testicle and hydrocele sac are delivered into the wound. The sac is then opened, and the fluid is drained. The redundant tunica vaginalis is then gathered or plicated with multiple sutures, effectively reducing the size of the sac and everting its fluid-secreting surface. The testis is returned to the scrotum, and the wound is closed.

- Jaboulay-Winkelmann Procedure (Excision and Eversion of the Sac): An incision is made along the anterior-outer surface of the scrotum through all layers down to the serous membrane. The testicle and hydrocele sac are delivered into the wound. The serous membrane (parietal tunica vaginalis) is incised longitudinally, often from the upper pole to the tail of the epididymis, and the fluid is evacuated. The redundant portions of the parietal tunica vaginalis are excised, leaving a smaller margin. The remaining edges of the tunica are then everted (turned inside out) and sutured behind the epididymis and testis. This prevents the reformation of a closed sac capable of accumulating fluid. The testis is placed back, and the scrotal skin is closed with sutures. This method generally has a low recurrence rate (around 1-2%) and few complications, is popular, and allows for a relatively short recovery period, minimizing time away from work.

- Bergman's Operation (Excision of the Sac): The initial approach to expose the testicle and hydrocele sac is similar. The sac is incised, and the entire parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis is resected (excised) close to its reflection off the testis and epididymis. Meticulous hemostasis (control of bleeding) is essential. The testicle is then returned to its scrotal position, and the wound is closed in layers. This technique is often preferred for hydroceles with very thick, fibrotic, or calcified sacs where plication or eversion might be difficult.

- Alferov's Method (Historical): This technique involved incising all scrotal layers and releasing the hydrocele fluid. For permanent drainage (marsupialization), the edges of the incised serous membrane (tunica vaginalis) were sutured to the edges of the subcutaneous tissue or skin incision of the scrotum. A bandage was then applied. This method is less commonly performed in modern practice.

Postoperatively, scrotal support, ice packs, and analgesia are typically recommended. Drains may be used temporarily, especially after more extensive excisions, to prevent hematoma formation.

Aspiration and Sclerotherapy

Simple aspiration of hydrocele fluid provides only temporary relief, as the fluid typically reaccumulates within weeks to months because the underlying fluid-secreting sac remains. It also carries risks of introducing infection or causing a hematocele (bleeding into the sac).

Sclerotherapy involves aspirating the hydrocele fluid and then injecting a sclerosing agent (e.g., tetracycline, doxycycline, phenol, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, polidocanol) into the empty tunica vaginalis sac. The sclerosant irritates the lining, causing inflammation and adherence (sclerosis) of the two layers of the tunica, thereby obliterating the potential space and preventing fluid reaccumulation. Sclerotherapy is less invasive than surgery and can be performed as an outpatient procedure. However, it may be less effective than surgery, with higher recurrence rates, and can cause significant scrotal pain and inflammation post-procedure. It is generally reserved for adult patients who are poor surgical candidates or who prefer a less invasive option and understand the risks and success rates.

Differential Diagnosis of Scrotal Swelling

It is crucial to differentiate a hydrocele from other conditions that can cause scrotal swelling or a mass, as their management differs significantly:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Hydrocele | Smooth, fluctuant, often painless (unless acute/tense) scrotal swelling that typically transilluminates. Testis usually palpable within or behind the fluid collection. Ultrasound confirms anechoic fluid within tunica vaginalis. Can usually "get above" the swelling. |

| Inguinal Hernia (Indirect) | Scrotal swelling that may extend from the groin, often reducible (can be pushed back into the abdomen, especially when supine), may increase in size with coughing or straining (Valsalva). Bowel sounds may sometimes be auscultated within the scrotum. Does not transilluminate if bowel or omentum is present. Usually cannot "get above" the swelling as it originates from the inguinal canal. |

| Spermatocele (Epididymal Cyst) | A smooth, firm, often small, cystic mass typically located at the head of the epididymis, superior and posterior to, and usually distinct from, the testis. It contains milky fluid with sperm. Transilluminates. Often asymptomatic. |

| Varicocele | A palpable collection of dilated veins within the spermatic cord, often described as feeling like a "bag of worms." More prominent when the patient is standing or performing a Valsalva maneuver, and typically decreases or disappears when supine. Usually occurs on the left side. Does not transilluminate. |

| Epididymitis / Orchitis | Acute onset of significant pain, swelling, redness (erythema), and warmth of the epididymis and/or testis. Often accompanied by fever, urinary symptoms (dysuria, frequency), or urethral discharge. The affected structure is very tender on palpation. A reactive hydrocele may be present. |

| Testicular Torsion | Sudden, severe, unilateral testicular pain, often associated with nausea and vomiting. The testis may be elevated ("high-riding") and lie transversely. The cremasteric reflex is usually absent on the affected side. This is a surgical emergency requiring immediate intervention. Does not transilluminate. Doppler ultrasound shows absent or markedly decreased blood flow to the testis. |

| Testicular Tumor | Typically presents as a firm, often painless, irregular mass arising from within the substance of the testis. It does not transilluminate. Requires urgent evaluation with scrotal ultrasound and serum tumor markers (AFP, β-hCG, LDH). |

| Hematocele | A collection of blood within the tunica vaginalis, usually resulting from trauma, surgery, or bleeding into a pre-existing hydrocele. Presents as a painful, tense scrotal swelling that does not transilluminate. |

| Scrotal Edema (Idiopathic or Secondary) | Diffuse swelling and thickening of the scrotal wall skin, often pitting. Can be due to local causes (e.g., cellulitis) or systemic conditions (e.g., heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, lymphedema). The testes themselves may feel normal within the swollen scrotum. |

Prevention of Complications and When to Consult a Urologist

While primary hydroceles cannot always be prevented, managing underlying conditions that might lead to acquired hydroceles (e.g., treating epididymo-orchitis promptly) can be helpful. For existing hydroceles, prevention of complications involves avoiding scrotal trauma.

Consultation with a urologist is recommended if:

- A new scrotal swelling is noticed, regardless of whether it is painful or not.

- An existing hydrocele becomes painful, rapidly increases in size, or shows signs of infection (redness, warmth, fever).

- The hydrocele is large and causes discomfort, cosmetic concern, or interferes with daily activities.

- In infants, if a hydrocele persists beyond 12-18 months of age, or if it is very large, tense, or associated with a suspected inguinal hernia.

- There is any uncertainty about the nature of a scrotal swelling.

A urologist can perform a thorough evaluation, confirm the diagnosis (usually with ultrasound), rule out other serious conditions like testicular torsion or tumor, and discuss appropriate management options, including observation or surgical repair.

References

- Elder JS. Disorders and anomalies of the scrotal contents. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Elsevier; 2020:chap 560.

- Wampler SM, Llanes M. Common Scrotal and Testicular Problems. Prim Care. 2010 Sep;37(3):413-26.

- Shadbolt C, Heinze SB, Dietrich RB. Imaging of groin masses: inguinal anatomy and pathologic conditions revisited. Radiographics. 2001 Oct;21 Spec No:S261-71.

- Dagur G, Gandhi J, Suh Y, et al. Classifying Hydroceles of the Pelvis and Groin: An Overview of Efficacy and Complications of Treatment. Basic Clin Androl. 2017;27:13.

- Ku JH, Kim ME, Lee NK, Park YH. The excisional, plication and fenestration techniques for the treatment of adult hydrocele. BJU Int. 2001 Jul;88(1):85-9.

- Ruben S, MacDonagh R. Complications of hydrocele surgery: a review of 200 cases. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1990 Apr;35(2):104-5.

- McAninch JW, Lue TF. Smith & Tanagho's General Urology. 18th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2013. Chapter 38: Disorders of the Testis, Scrotum, & Spermatic Cord.

- American Urological Association. Evaluation and Treatment of Cryptorchidism (2014) and Evaluation and Management of Hydroceles in Infants and Children (Clinical Guideline Statement). (Refer to latest AUA guidelines).

See also

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Cystitis (Bladder Infection)

- Hydrocele (Testicular Fluid Collection)

- Kidney Stones (Urolithiasis)

- Kidney (Urinary) Syndromes & Urinalysis Findings

- Bilirubinuria and Urobilinogenuria

- Cylindruria (Casts in Urine)

- Glucosuria (Glucose in Urine)

- Hematuria (Blood in Urine)

- Hemoglobinuria (Hemoglobin in Urine)

- Ketonuria (Ketone Bodies in Urine)

- Myoglobinuria (Myoglobin in Urine)

- Proteinuria (Protein in Urine)

- Porphyrinuria (Porphyrins in Urine) & Porphyria

- Pyuria (Leukocyturia - WBCs in Urine)

- Orchitis & Epididymo-orchitis (Testicular Inflammation)

- Prostatitis (Prostate Gland Inflammation)

- Pyelonephritis (Kidney Infection)

- Hydronephrosis & Pyonephrosis

- Varicocele (Enlargement of Spermatic Cord Veins)

- Vesiculitis (Seminal Vesicle Inflammation)